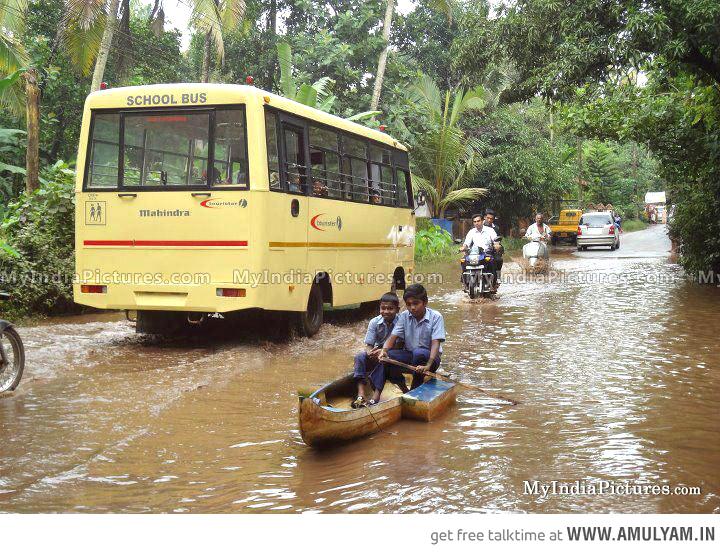

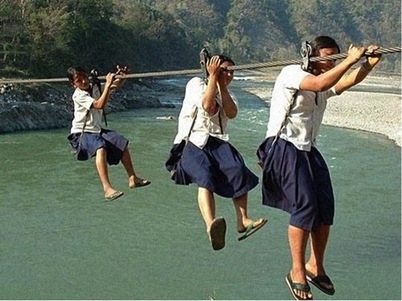

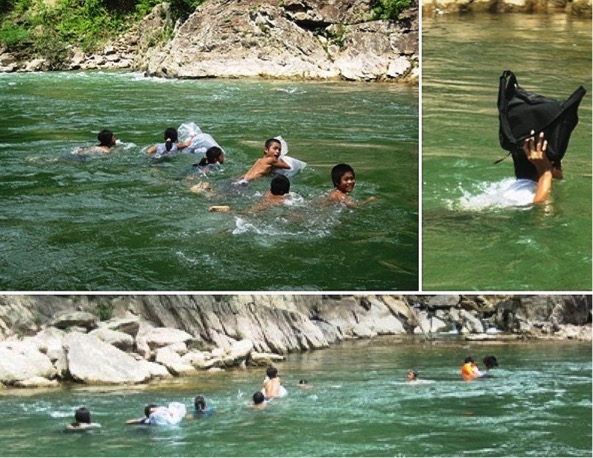

The challenges are often economic, as families need their children working to feed everyone or can't afford books, tuition, and school clothes, etc., but sometimes, geography gets in the way, too. According to UNESCO, children living in a rural environment are twice as likely to be out of school than urban children, and when you add in jagged mountains, isolated valleys, raging rivers, and flooding in the monsoon season, it can be almost impossible for some kids to get to school.

ALMOST impossible. As they 25 examples in photos will demonstrate, some kids will do just about anything to get to school, risking their very lives just to get an education because they know it's their only chance at a better life.

We can all draw inspiration from their sacrifice and dedication, and the next time your kids complain about getting on the school bus, just show them this blog!

With love,

Norm :-)

PS Contact me if you're interested in helping kids like these and others around the world get an education.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed