Mildred and Richard Loving were woken up abruptly in the early morning hours of July 11, 1958.

Someone was in their bedroom, standing menacingly over the bed. The couple, sharing their marital bed in their own home in Central Point, Virginia, reached for their clothing, at first thinking the interloper was a burglar.

“Get up!” the voice barked, training a powerful flashlight in their eyes. “Y'all both under arrest.”

“What did we do?” Richard protested, shielding his wife.

“That ain’t valid in Virginia!” the officer spat, marching them out of their house in handcuffs and placing them in a waiting squad car.

The young couple was transported down to the local station, where they were booked and charged with Sections 20-58 and 20–59 of the Virginia Code and thrown in the same cells that were used to house hardened criminals.

They soon found out that the police raided their home in those early morning hours based on an anonymous tip. Hurling insults and racial epitaphs at them, they learned that the police hoped to catch them in the act of having sex, since that would have brought additional criminal charges.

They were married and happened to be an interracial couple.

Since Richard was white and Mildred was “colored” as it was called in those days – a mix of black and Native American - that was enough for the police to lock them up in Virginia.

In fact, Section 20-58 of the Virginia Code made it a crime for couples of different races to be married (referred to as ‘miscegenation’) out of state and then return to Virginia.

And Section 20–59 classified miscegenation as a felony offense, which came of a prison sentence of one to five years.

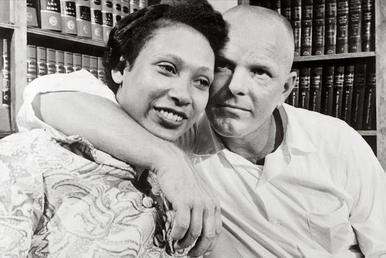

Mildred Delores Loving was born July 22, 1939 there in Virginia. Ironically, there may be some confusion as to her racial origins.

During her drawn-out legal nightmare, she identified as African American (or black or “colored” in those days).

But the night she was arrested, she told the police that she was “Indian” and later on, claimed to be Indian-Rappahannock. However, she may have denied being partially black to try to deflect the charges, since the intent of these laws left over from the Jim Crow era was to separate African Americans and whites.

We do know that she was a soft-spoken, gentle, and a pretty woman, growing up in the same small Virginia community of Caroline County where she eventually met her husband, Richard Loving.

Richard, born October 29, 1933, came from a family that owned seven slaves according to the 1830 census, and his grandfather, T. P. Farmer, fought for the Confederates in the Civil War.

But in their small community, there was more racial harmony and mixing than we might guess.

“There’s just a few people that live in this community,” Richard described, who looked like the typical young southern white in those days with a blond crew cut. “A few white and a few colored. And as I grew up, and as they grew up, we all helped one another. It was all, as I say, mixed together to start with and just kept goin’ that way.”

In fact, Richard's father was a loyal 25-year employee of one of the wealthiest black men in the U.S. at the time, and a lot of Richard’s best friends were black or racially mixed, including Mildred’s older brothers.

Either way, Richard and Mildred met in high school and quickly fell in love, becoming inseparable. When Mildred became pregnant at the age of 18, Richard even moved into her family home.

Knowing full well that it was illegal for them to marry in Caroline County due to Virginia's Racial Integrity Act, the young couple traveled to Washington, D.C. where they could legally marry.

They came back to Virginia several times to visit family in Central Point, and it was during one of those visits in 1958 when the police barged into their bedroom in the wee hours and arrested them.

The racial climate in Virginia was all-too-typical in those days. In fact, out of all 50 states, only nine did nothave a law against interracial marriage at some point. And by the 1950s, the majority of U.S. states (and every single state in the south) had a law against miscegenation.

There had been laws against racial mixing or marriage all the way back to the colonial era, which were renewed during Jim Crow. Most of the laws focused on keeping black men away from white women. The rape of black women by white slave owners or men was commonplace, leading to the "one drop of blood" rule (if someone had even one drop of African American blood, they were considered black in the eyes of the law).

But those laws were far less barbaric than trial-by-mob, as black men were frequently attacked or lynched for even talking to a white woman.

The law and courts held no refuge nor justice. The case of Pace v. Alabama in 1883 went all the way to the Supreme Court, where an Alabama law against anti-miscegenation was deemed fully constitutional.

And in 1888, the Supreme Court ruled that states had the legal authority to prohibit or regulate marriage based on race.

In Virginia, that was codified in 1924 with the Act to Preserve Racial Integrity, with violators facing a prison sentence of one to five years in the state penitentiary.

By the time the Lovings were pulled out of their bed and arrested, 16 states still had anti-miscegenation laws on their books – most of them in the south.

Sitting in jail and with no resources or recourse to fight the charges, the Lovings both pleaded guilty on January 6, 1959. Their crime was officially documented as "cohabiting as man and wife, against the peace and dignity of the Commonwealth.”

Per the Act to Preserve Racial Integrity, they were sentenced to one year in state prison, but the sentence was suspended when they agreed to leave the state of Virginia and not return.

Happy to evade a prison term but sad to leave the community and people they grew up with, the Lovings fled to the District of Columbia, settling into a D.C. ghetto. They were poor but lived in peace, and raised their three children, Sidney, Donald, and Peggy, there.

But they had increasing financial difficulties and missed their home and families. When one of their sons was struck by a car in the streets of D.C. (he lived and recovered), a frustrated Mildred wrote a letter to the young Attorney General of the United States, who she thought may be sympathetic. In the letter, she documented the Lovings' plight.

She never expected to receive a reply, but she did hear back from that Attorney General - Robert F. Kennedy. Of course, Robert’s brother had been the progressive President John F. Kennedy, Jr, who had been assassinated a few years earlier in 1963.

Robert Kennedy connected Mildred with the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU), who agreed to take on her case.

The ACLU assigned two volunteer attorneys, Bernard S. Cohen and Philip J. Hirschkop, to the Lovings' case. They filed a motion to vacate the criminal judgments in Virginia’s Caroline County Circuit Court, stating that the Act to Preserve Racial Integrity violated the Fourteenth Amendment's Equal Protection Clause.

After nearly a year of waiting with no progress, the pair of ACLU attorneys filed a class-action suit in the U.S. District Court for the Eastern District of Virginia.

After hearing the case, Judge Leon M. Bazile ruled against the Lovings, including this statement:

“Almighty God created the races white, black, yellow, malay and red, and he placed them on separate continents. And but for the interference with his arrangement there would be no cause for such marriages. The fact that he separated the races shows that he did not intend for the races to mix.”

The ACLU appealed Judge Bazile’s decision in the Virginia Supreme Court on the grounds that it violated the constitution. However, in 1965, Justice Harry L. Carrico wrote an opinion for the court that upheld the constitutional legality of anti-miscegenation laws.

Finally, the Lovings and the ACLU appealed the decision to the U.S. Supreme Court, Loving v. Virginia, 388 U.S. 1. While Mildred and Richard were not in attendance as their lawyers made oral arguments on their behalf, Bernard S. Cohen passed on a message from Richard Loving: "Tell the Court I love my wife, and it is just unfair that I can't live with her in Virginia."

On June 12, 1967, the United States Supreme Court came back with their ruling. With a unanimous 9-0 vote, the highest court in the land overturned the Virginia criminal conviction and deemed anti-miscegenation laws unconstitutional.

The Supreme Court opinion, written by Chief Justice Earl Warren, struck down any laws regulating interracial marriage since they violated Equal Protection and Due Process Clauses of the Fourteenth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution.

At least on a federal level, it was no longer illegal for racially-mixed men and women to marry, thanks to the Lovings and their attorneys.

The landmark case was one of the most significant civil rights wins to date in the United States, at a time when civil rights leader Martin Luther King Jr. was assassinated the very next year.

I wish I could tell you that the Supreme Court ruling changed things, rooting out racism in U.S. society, but we know that's not the case. Despite the Supreme Court ruling, many states resisted, begrudgingly changing their laws against interracial marriage – if at all.

In fact, Alabama was the last state to accept the Loving vs. Virginia ruling, not removing its anti-miscegenation laws until 2000.

That’s not a typo; it was still technically illegal for people of different races to marry in Alabama only 20 short years ago.

In the movies, the courageous defendants stand proudly in the Supreme Court alongside their lawyers. But in real life, it rarely works that way.

Instead, the Lovings lived on a quiet farm in Virginia during much of the prolonged legal battle, trying to stay out of sight (to avoid the media as well as a safety precaution). But after the Supreme Court decision, they moved the family back to Central Point, where Richard built a small house and they raised their children in relative peace.

In 1975, Richard was killed when he was hit by a drunk driver while driving in Caroline County, Virginia. He was only 41.

Mildred was in the car with him and lost her right eye in the accident but lived. She passed in 2008 of pneumonia in her home in Central Point at the age of 68.

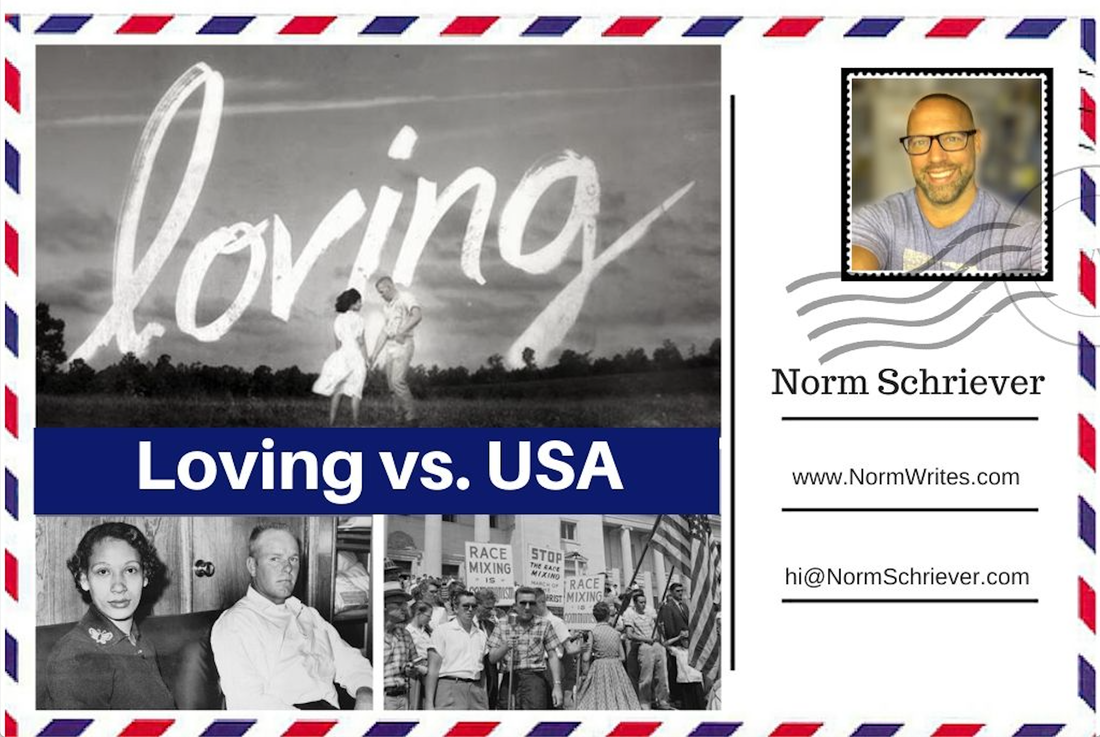

We’re not sure if Richard and Mildred fully realized the societal and cultural shift they’d started. Over the decades, their story has been the subject of several songs and three movies, including Loving, which debuted at the 2016 Cannes Film Festival.

Their case also served as a precedent for other civil rights cases since, including Obergefell v. Hodges, a landmark 2015 Supreme Court decision that lifted restrictions on same-sex marriage.

In 2014, Mildred was honored posthumously as one of "Virginia’s Women in History,” and in 2017, a historical marker was dedicated to her in front of the building that formerly housed the Virginia Supreme Court of Appeals.

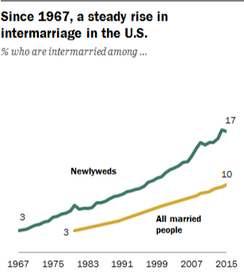

Back in the 1960s, 0.4% of all U.S. marriages were between interracial couples. By 1980, that number had increased to 3.2% of all marriages, and then to 8.4% in 2010.

Today, about 19% of all newlywed marriages are between interracial couples, or almost 1 in every 5.

By 2050, there will be so many multi-racial people that the vast majority of marriages could be considered interracial, although we probably won't even bother keeping track of that statistic anymore.

To recognize the sacrifice and plight of Richard, Mildred, and many others like them, June 12th – the day of their Supreme Court decision - has been designated Loving Day in the United States.

-Norm :-)

P.S. Thank you for sharing so we can try to spread some positivity and understanding.

***

This blog is dedicated to my old friend, Kyle McGee, who taught me so much.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed