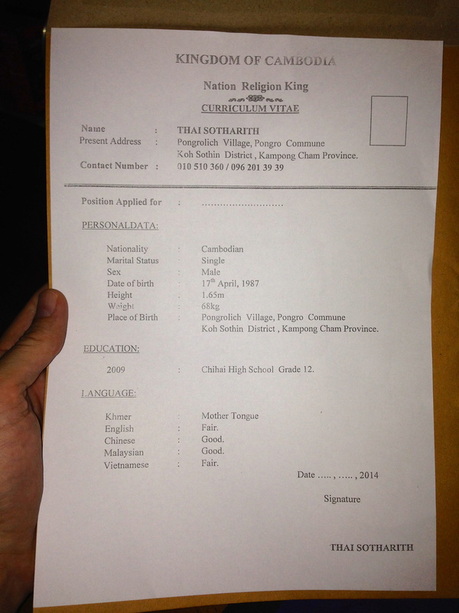

| This is what a resume looks like in Cambodia. I was sitting at a bar, eating some grub on my last evening after a 4-month stay, and got to chatting with the bartender, a pleasant local woman. She pulled out this resume and looked it over and showed it to me, since I was the only person in the bar. She remarked that the young man who submitted the resume must be from the province because he really has no work experience and not even a photo to submit. There are really no jobs in the province, she explained – they’re all in the main cities and especially areas of tourism like Siem Reap and Angkor Wat (a world heritage site,) Phnom Penh, and the beach town of Sihanoukville. So everyone comes to those “big city” or tourism areas to try and make a living. “He did graduate high school,” she said, “The most important thing on resume – any resume – is that he speak a little good English. So |

I asked her how much an entry-level job at the bar might pay.

“$60 or so,” she said.

“A week?” That seemed like a pretty good wage for Cambodia.

“A month.”

Imagine working 12 hours a day, 6 or 7 days a week for $60, or less than $2 a day? Yet that’s what the vast majority of people in Cambodia earn every month – if they’re lucky. That’s about the going rate, whether they are servers at restaurants, tuk tuk drivers, give massages, do construction or sew and work in a laundry. The bartender told me that so many young people come to the city try and get these jobs. They have no place to stay, no family or friends or even a dollar of savings to fall back on once they arrive, so they sleep 10 to a room in a shabby guesthouse, on the floor where they work, or even on the street on a hammock.

They send as much money as they can manage back to their families in the province – the only system of social security for older people. The financial pressure on these young people is enormous. Sending $30 home can make the difference between their parents, grandparents, and whole extended families having enough to eat or receiving medical care or not. Too often, they are forced into doing jobs their parents would be ashamed of, compelled to hide their vocation but still needing to send money back for them to survive.

They always start their tenure in the city and at a new job sending money back, but some are pulled into dark temptations – partying, buying nice clothes and phones, and always drinking. Since any real money to be made is at a bar, club, or working to pacify the tourist’s desires, alcoholism is such an unquestioned fact of life that nearly everyone drinks all night, every night. The depression of hopelessness is staved off by taking a shot and the energy of another night’s neon song. The girls in bars, whether bartenders, hostesses, servers, or “bar girls,” make a significant portion of their income on tips or lady drinks. If they can convince a foreigner to buy them a drink (at an inflated price,) they get paid handsomely, usually $1.50 or $2, or as much as they would otherwise earn all day.

The girls mostly come to work as these bar girls, or that is where they always end up, where they can earn more and try to attract the favor of a foreigner for some nice meals, a vacation, a brand new phone. Especially the phone - it seems like having a nice new Android or (gasp!) iPhone is a badge of wealth to these girls. But it’s also a tool to allow them to attract and keep in touch with foreign boyfriends, even when they go back overseas. Keeping that relationship alive can be lucrative – guys often send a hundred dollars a month or so back to their “girlfriends.” Or, if things go really well, they may pay for them to take English classes or go to university. If they’re really lucky, they’ll find the Holy Grail – a visa to another country. The only detail is that they need to marry the guy, but that is a small inconvenience. Sometimes, it takes a week for the marriage to manifest, sometimes, years. It matters little if they know the guy well, are attracted to him, or even like him – the opportunity for economic security and the chance for a better future for them and their family is like a winning lottery ticket that just needs to be cashed on a daily basis.

For many of them, the devil arrives in their lives and his name is Yaba. That’s what they call the Southeast Asian version of methamphetamines, or ice - a terrible concoction of poisons that eats away at their brains when smoked – but let’s them float above their problems for a few precious hours. Once they get hooked on Yaba there’s usually no going back, eventually becoming reckless with selling their bodies. When that happens, all their money goes to their habit and less and less back to their families. If they get pregnant they usually go back to the province to have the help of their mother until they deliver. When they come back to the city to work, the baby usually stays with grandma.

Even those working outside of the bar scene make a significant portion of their income on tips and kickbacks. So if the tuk tuk driver suggests a hotel and delivers the tourist to the front door, they’re entitled to a tip from the hotel for bringing a booking. Sometimes the drivers have a pretty good day, but too often they’re lucky to have one fare for a buck or two. For that reason, they’ll assault your senses with offers to take you to every tourist attraction. You usually have to say ‘No,” three or four times to every single street vendor or tuk tuk driver just to get them off your back. It’s hard not to get annoyed at their aggressiveness but once you understand the economics of the their situation, you tend to soften your stance.

And then, there are the hustlers; battalions of forgotten people working the streets, outside of any rules or structure of the tourism industry. Adults – sometimes even their own parents - send children barefoot into the street to beg all day and all night, armed with sad eyes and wearing dirty rags, just enough English to tug on a sympathetic tourist’s heart strings. Maybe they sell bracelets or knick-knacks, but they’re really just seeing how much they can squeeze out of each farang - foreigner.

How can you blame them? That watch you’re wearing costs more than they make in a year, what you spend on a Saturday night enough to feed their family for a month. The only problem is that most of the money goes to the grown person around the corner who’s spending it on booze or cigarettes, and not much to the kids working in the razor sharp streets.

Some bar girls – who are sick or too hooked on Yaba to work in bars – work as freelancers. Of course there are pickpockets and those who set tourists up when their pants are down (literally) but the vast majority of all these people are good, honest, and hard working – even when faced with unfathomable poverty. They set up a chair and give haircuts in the street, or drag along a cart of coconuts to sell, a machete and straws the tools of their trade. Many just set up a blanket in the dirty street and sell icy fruit drinks, animal innards roasted over a coal fire, or dried fish. It’s all they know, and without skills, education, or any resources, it takes all of their life’s energy just to live hand to mouth. But they are honorable people - they’d split their last grain of rice with you if you were in need.

“How long have you been working here?” I asked her as she took my plate away and put another ice cube in my beer.

“Three years now,” she said. “Good job and nice owner that like me work.”

“And how much do you make per month?”

“$80,” she said. And this was a decent Western bar in tourist areas that catered to foreigners and she spoke good English. Imagine what the older lady in back made, homely and without strange words, so resigned to mopping up and cooking my meal?

I wondered what would become of this kid who was applying for the job, even if he got it? Faceless and with nothing to claim except a blank page, what was his fortune? Or so many countless young, cheap laborers like him who came to the cities? I guess we could just be thankful this new generation didn’t have to experience the horrors of war and genocide that their parents endured. But as tourists keep pouring money into the country, I just wished that more of it actually landed with the real people living and dying in the streets, who really deserved it. I guess I always hope that things get a little better.

“Ketloy,” I said, asking for the bill in Khmer – the Cambodian language. She smiled and brought me the bill. I put down enough to cover the bill and a tip big enough for her to eat for a month and handed it back to her She went to give me change, confused why I overpaid.

“Keep it,” I said. “That’s a tip for you and spilt it with the lady over there with the mop.”

“What? Really?! Oh thank you thank you! Ohn Kuhn, bong!” she said to me, holding her hands to her forehead and bowing slightly to the sky, an offering to Buddha thanks for her good fortune.

I smiled back – a real smile that I hope she remembered when times were bad. I thanked her again and walked out onto the street.

“Tuk tuk?! Tuk tuk! Where you go? Angkor Wat?” five taxi drivers barraged me at once. I checked my watch – I had to head to go collect my bags at the hotel and get to the airport soon.

I guess that’s really what it comes down to – some of us are lucky enough to have places to go while the rest of us are always left hoping things get better, praying fortune arrives if they could just get through another day, around the corner or maybe in the kindness of a stranger. Either way, none of it still makes any sense to me. But that’s just how it is.

-Norm :-)

RSS Feed

RSS Feed