Of course I did, since I’m writing this to you now, several months later from my safe and comfy confines on the mainland in Manila.

But that wasn’t always a foregone conclusion – at least, in my mind.

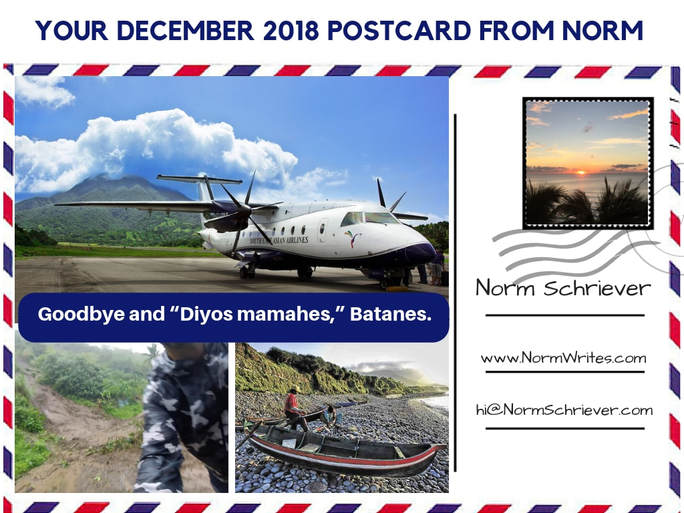

Yet, almost a week after arriving and being stranded by not one but two typhoons, I would hop on a sturdy twin-propeller airplane and pray with the rest of the passengers as the clouds rushed to overtake the morning sun. It was a brief respite, the only time it hadn’t been too windy and rainy for airplanes to take off or land.

Each morning, the hordes of stranded travelers would start queuing up at the airport at 4 am, waiting for the doors to open so we could jockey for a spot on the first flight out at 10am.

And each morning, they were canceled as the crowd, exhausted, disheveled, and increasingly concerned, letting out a collective groan when the loudspeaker announced the bad news. Some people cried. After a while, they were all familiar faces, just wearing different dirty laundry, placing their bags in line instead of standing so they could go sit somewhere comfortable or try to sleep.

I’d grumble as I shuffled back outside, too, grabbing the same trike driver to my same hotel, where they handed me the key to my same room. The hotel was still empty except for one other couple, and I found the personal effects I meant to leave behind waiting for me, neatly lined up by the understanding staff.

I wasn’t playing around anymore, and proactively booked four flights over the next four days just in case one of them managed to get out. To pass the time, I walked around the main town of Basco in the rain – just a dot on a map itself – and bought pizza for the nice gals working at the hotel, who taught me to say thank you in their indigenous Ivatan language – “Diyos mamahes,” or “Thank you God.”

As the plane lifted off, banking dramatically to avoid the steep mountains overlooking Basco and head out over the vast and windswept sea that separated Batanes from the mainland, the passengers cheered, prayed, and hugged each other. I closed my eyes, the rattle of the propellers comforting, feeling the sun on my face as I recalled one of the best moments of my life I’d just experienced on the island…

Out this far, I didn’t see anyone except a smattering of local inhabitants. Most (sane) tourists were comfortably bunkered down in their hotels in Basco, staying indoors as they watched news reports that were growing increasingly dire. A Super Typhoon rushed towards the island on a certain collision course.

That sounded like the perfect day to go on a tour of the island to me, as I’d rather face the elements that spend another day in my Spartan hotel room watching my clothes not dry.

But this had quickly escalated past “uncomfortable yet adventurous” to “Whoa, sh*t just got real."

I could even sense the urgency of my guide, as the road was abandoned past the village, with only open highway along the coastline as we raced against the storm…

"We go into the mountains now," he answered, kick-starting the motorcycle, eager to get rolling before I was even entirely on board. I realized that he wasn't going to cancel our tour no matter what conditions we faced, as he was desperate for the $18 fee since it was the rainy season and there were few tourists.

Before I could voice my reservation that we should err on the side of caution and assure him that I was happy to pay-in-full, only five minutes outside of the village, we ran into a bigger problem.

I turned to look at a wall of earth rushing down at us.

Of all the things I worry about while traveling and living abroad – Dengue and Malaria, robbers and kidnappers, hurricanes and cold-hearted temptresses, I’d never even considered a landslide.

But there it was, clicking in my mind within a split second as a river of mud, rock, earth, and water dislodged from the slope, snapping trees and shrubs with hardly a crackle and picking up bowling ball-sized boulders as it channeled at us.

It came fast. There was no time to do anything, even as I saw it and registered what was going on. The only reaction my driver had was to hit the brakes – which was the right move since it was barreling right towards us.

And then, it hit, sprawling across the highway that had been pristine a split second earlier, slowed only by a stone wall standing on the far side, smashing the stones and mortar in two like it was a toothpick, and then settled. It was quiet.

I realized then that my GoPro was still on for some of it, but the few images that were salvageable don't come near to doing it justice.

We looked at each other in stunned amazement, and that split second felt like 10 minutes. My memory of the next few minutes is blurred, but I do remember stepping out of the trike, first with one flip flop that got sucked into the mud, and then, barefoot with my other step.

Taking cues from my driver, I realized that we weren’t out of harm’s way yet. In fact, we were smack dab in the path of calamity, with our trike rendered incapacitated wheels-deep in mud and the hillside loosened to the point where a second washout was highly likely.

Without saying a word, we both hopped to action, jumping out and rocking the trike back and forth until the wheels were cleared so we could spin it around and half carry/half wheel it back a few feet, where only shallow mud and stones littered the highway's surface. From there, we could easily roll it a few feet more, wipe our brows, and take in the scene.

Still in shock but resplendent that we’d escaped unharmed, we made our way back to the hamlet only a few minutes away, as the road forward was now impassable.

I was slightly relieved that we'd both agreed upon canceling the rest of the tour, as we’d be much safer back in Basco. Heading back through the hamlet, we barely slowed long enough to tell a few passersby's what happened and warn them that the road ahead was out.

| | |

Several motorists on the other side of the landslide fifty feet away shrugged and turned around, while others sat there and tried to calculate if there was a way to get through. There wasn’t.

This was the only road back to Basco – to safety from the screaming wind and driving rain, but we were forced to turn back towards the hamlet, boxed in between two landslides.

A well-built, smiling man in his late 20s came out and after hearing our story in rapid-fire Ivatan, eagerly brought us up to his apartment, where he brought out two dry shirts and cups of coffee.

Thanking him profusely, I squeezed into the too-small shirt and muzzled the mug of hot coffee to warm up my hands, giving my windbreaker to the driver.

Uncle Joey was born and raised right there but had made it over to Saudi Arabia for a few years to work construction, which allowed him to build this store and apartment for his family when he returned, as well as start his own little construction company.

The three of us watched as police and local service workers clamored back and forth with trucks and shovels.

Boy did he like to talk, and we basically exchanged life stories in that half hour…and then hour…and then hour-and-a-half wait.

I must admit that I was a little impatient, as if I relied on the local sense of timing and urgency, we would be content just to sit there and chat and drink beers all night.

But every time someone came back to the hamlet, on a bicycle, motorbike, or just a farmer pulling his cow by a rope so that he could keep it in his house during the storm, they said the same thing: the road was not clear.

There was no way I wanted to spend the night there in that hamlet to ride out the storm, so I talked them into venturing out from our dry (if not warm) shelter and figuring something else out. My driver would leave his trike here in the hamlet, which he could pick up the next day or whenever it was possible again - the trike was just too wide and clumsy to navigate the narrow and muddy conditions. Instead, Uncle Joey would drive us on his much sturdier motorcycle with off-road tires.

To his credit, he came up with an ingenious – yet risky – strategy. One by one, he’d drive us to the edge of this landslide.

From there, I’d have to get off and walk across on foot. On the other side, I’d look for a motorcycle, car, or truck that was turning back towards Basco and hitch a ride with them. Although the plan sounded a little indefinite, it was better than sitting and waiting all day (and probably night) in the hamlet.

I got off the bike, thanked Uncle Joey for his hospitality, took off my flip flops and started making my way across the landslide. It was treacherous going since the mud was two feet deep in places and you sank right in, stepping on rocks and sharp sticks as you went. But my biggest concern was that the eroded hillside spilled more of its contents onto the same pile, which could be a serious problem or even deadly if I was stuck in the middle of it.

I tried to double-time it across the landslide but there was only one speed, and rushing just made me fall, so it took me a few minutes to cross, adrenaline pumping and covered in mud when I reached the other side.

Joey was headed back to get the driver, so I looked for a motorist I could hitch a ride with but saw none. I started walking.

I had the coastal highway completely to myself, and soon I found out why; after walking for only fifteen minutes or so, I came across another landslide.

Again, I took off my flip flops and braced myself and double-timed it across before more debris might rumble off the hillside at me. There must have been several landslides along the snaking 20km or so coastal road to Basco because I didn’t see one car, bike, or person along the way now.

I didn’t even know if my driver and Joey were coming back, or if they decided to wait it out. I just knew that safety was ahead in Basco, and I better get there quick as the sky continued to darken and spiral in a preternatural fury.

Resigned now that I might have to walk most of the way to town, I took off my flip flops for good this time, put them in my waterproof SCUBA dive bag slung across my shoulder, tightened the drawstring on my shorts, and started running.

The rain whipped my eyes, stinging them nearly shut. Pebbles, sticks, and wind-swept debris scuffed my feet with each step.

The drone footage of my consciousness zoomed in, and then out.

On a small, exposed island in the middle of the Pacific Ocean and South China Sea, about as far across the world as you can go without falling off and disappearing.

No idea where to go except in one direction following that road.

Not one single person around me.

Running in the middle of a typhoon, soaking wet and barefoot along the yellow line in the middle of a vast highway,

Dancing armies of palm trees and muddy green hills on one side of me,

The ocean boiling violently on the other; a giant’s teapot forgotten on the stove, threatening to swallow the island and every insignificant soul upon it.

But there was no fear; only exaltation, like a man struck twice by lightning wakes up every morning after.

I was no longer cold, but every hair on my body stood up. I’m no runner, but each time I met the pavement, I sprung back up, surprised by the surge of energy that coursed through my body.

I saw it all so clearly. The gears of time slowed until there was only that moment.

There was only one more step; one more breath.

I was alive.

ALIVE!

I left out a wolf howl from deep within me and quickened my pace, still, breathing in the chaos and exhaling calm, the closest thing to nirvana I’ve ever known.

Although I was determined to hoof it back to Basco if needed, after climbing through mudslides and running on the abandoned highway only for about half an hour, a motorbike came up behind me. It was my friends – Uncle Joey and the driver – who greeted me warmly, as the path was cleared enough for them to navigate through.

It still was an adventure getting “home” to Basco that day, with lots of hitchhiking, paying a few coins for trikes and jeepneys to take us as far as they could, waiting outside bars and local shacks as they readied themselves, passing harrowing roads littered with boulders and cascaded with dangerous waterfalls, and plenty of shivering.

But, eventually, I did make it back, and a lukewarm shower, a change of clothes, and a hot meal never felt so good. And I'll carry with me always the feeling I had on that road that day – and the ultimate lesson I learned in Batanes; that even in this day and age, there are still places on this earth where you can be wild and free.

“Diyos mamahes,” Batanes.

Norm :-)

RSS Feed

RSS Feed