| I jump rope everywhere I go. I learned when I did a little boxing training in Sacramento years back, and I’ve always liked it. I absolutely abhor running and don’t particularly love getting punched in the face, so skipping rope became my feel good part of the workout – my mental rest. So I got pretty good at it, honing my skills over the years until I could ‘rope’ smoothly like I was dancing. When I left the U.S. almost three years ago and moved to places like Costa Rica, Nicaragua, and now all over Southeast Asia, the jump rope came with me. In places where you never know when you’ll find a gym or a suitable place to work out, the rope comes in handy. One of my favorite things here in SE Asia, especially in the main cities, is that they always have big public parks – tile-floored promenades lining the river or ocean and everyone comes out to exercise at sunset. Sometimes there are thousands of people packed in – playing badminton, chasing their kids around on their bicycle, ridiculous group dance fitness classes, football games, and other crazy Asian yoga-gymnastic stuff. At first I was shy to go out there and work out with them – you’re conspicuous enough as a foreigner in Asia without sweating and jumping around – but I did find a corner of the plaza to take out my jump rope and go to work. After a while, I grew to love it. People did point or stop and stare, or walk but it was all out of fun - a lot of them have never even seen someone jump rope, so they were enthralled. Whole families would comer over and show their little ones, old ladies would watch for a while and give me the thumbs up, and little kids would gather around and laugh and replicate the moves without a rope, as enthusiastic as if I’d shown them a magic trick for the first time. It was my way of connecting with the community – the real people, not the tourist façade, and people would stop to say hello or talk and I’d offer them the rope to try. Sometimes, so many people gathered around that I seriously considered putting out a tip cup for noodle money! I jumped rope in public parks in places like Nha Trang, Vietnam, Phnom Penh, Cambodia, Boracay Island in the Philippines and Phuket, Thailand. But none were every as special as when I jumped rope here in Luang Prabal, Laos yesterday. A charming town along the Mekong River in northern Laos, Luang Prabal is known for it’s French colonial architecture, Buddhist Wats, or temples, and night markets full of dazzling hand crafts and good eats after lazy, hot afternoons. Of course I wanted to exercise every day so I looked for a gym. There were internet posts from 2012 about one on the outskirts of town, but it took me an hour to walk there and I never found it so I kept walking and hiked up a big hill instead. But I found the perfect spot to work out in town – right on the main avenue there’s a small park that’s the entrance to a steep set of stairs up the mountain to a statue of Buddha where you can get a view of the whole town. The park had a tile floor, wasn’t too crowded, and had the most incredible view of a huge Wat across the street, with purple trees and gold lined rooftops. I started going there each late afternoon to jump rope and sprint up the stairs up the mountain, which almost killed me but was great sport, dodging hordes of camera-snapping Japanese tour groups on the way up. On that same avenue they set up the night market every day, so around 5 pm you’ll see hundreds of red and blue-topped tents erected and the locals spreading their wares out on blankets to try and make a buck of tourists – incredible jewelry, cheap t-shirts, pirated DVDs, and more than a few Laos bakers who brought out donuts or coconut cakes. Since it was a tourist hotspot at night, the street kids came out, too – trying to collect bottles and cans for change or sell little trinkets and bracelets, though no one begs. They come up to the park, too, and started watching me jump rope. In between sets, when I went to run up the stairs, they held my rope and tried it themselves. Sheer hilarity ensued, and after a while I was spending so much time teaching them how to jump and there were so many kids who wanted a turn, I wouldn’t even get to use the rope again. I didn’t mind – the sheer joy on their faces was worth it. Most of the kids just played around and stumbled and fell and it was a fun joke but the other day two little girls, barefoot and dirty, out on the street peddling something, stood close by and watched as I skipped rope. I offered the rope to them but at first they were super shy – Laos culture is extremely conservative, especially for females, but their curiosity got the best of them and one brave girl took the rope and tried. To my amazement, she jumped really well. It wasn’t smooth of course – she had no technique but was just going off instinct – but I’d stop and show her how to do one thing and then give the rope back to her and she’d copy it. Soon she was able to crossover like a champ – the move where you lower and cross your hands so the rope takes a big infinity symbol path around you. I couldn’t believe my eyes – soon she was doing ten crossovers in a row, something I can’t even do after years of jumping rope! Her friend was really good too, but this one girl just had a look in her eyes like she’d found something that transported her. She was jumping barefoot on a hard surface and her feet were so beat up they were almost bleeding, but she was having so much fun she couldn’t stop. I knew she’d be jumping rope the rest of her life if she could The sun was going down and I was ready to puke a lung after running up the mountain 5 times so I told them I had to go. But I’d be back 6pm the next night if they wanted to jump more. They beamed ear to ear and agreed enthusiastically, high fiving me before going off to work all night. The next evening I came again, but not to jump rope, myself, because of a nasty cold. I greeted the girls with chocolate cupcakes I’d bought for them and then we got down to the business of ‘roping. I handed it over and took out my GoPro and took a few shots of them skipping rope right in front of the Wat across the street. They didn’t have time to warm up so they weren’t quite as good as the day before, but still it was amazing for total beginners. Toward the end of our twenty minutes together, the one girl even tried double-unders, where you jump up and twirl the rope around you twice and land and keep going, something that’s pretty difficult. She got it on her last try, and was so psyched that she almost ran up to hug me like a proud daughter! I knew I was leaving for Thailand the next day and there was no way I could leave them without a chance to jump rope again after seeing how much it meant, so I handed them my jump rope. After all I’ve been through with that rope, all the places we’ve gone together and the things we’ve seen, it was like giving away an appendage – like a baseball player giving his best lucky glove to a young fan. They weren’t sure what I meant by the gesture but I assured them that the rope was now theirs, a gift. They assured me they would share it, and I snapped a photo of them holding it before high-fiving and leaving them to the sunset. So if you happen to travel to the end of the world, a little riverside town in Laos with golden temples and hot French afternoons, and you see two little girls jumping rope on the side of a mountain near a brilliant purple tree, with big smiles on their faces as Buddha watches over, you’ll know how it all began. Norm :-) | My little jump rope students holding up their new rope! |

|

0 Comments

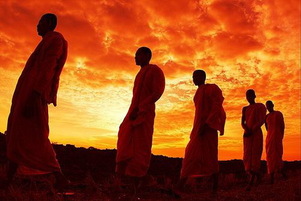

I hadn’t seen rain in 5 months, so when I woke up to wet streets here in Luang Prabang yesterday I headed out for a walk. That’s one of my favorite parts of traveling – throwing on a pack with a bottle of water, putting on my headphones, and hitting the road with no destination in mind, a karmic exercise in trying to get lost. So I laced up my battered Nikes and marched toward a ridge of emerald mountains north of town. The road went from smooth pavement to bumpy stones then dirt roads and there were no tourists anywhere but plenty of roosters chased by mean dogs chased by barefoot children, farmers drying their red, yellow, and green chili peppers in the sun, and dirt-faced vendors grinding sugar cane, all looking me up and down as I walked by. I finally came to the base of the mountain and headed up a steep logging road. When it ended, I found a footpath that led blindly into jungle groves. I followed and soon found myself in a meadow where the whole forest floor was burnt – walking on black ash like the side of a volcano. Finally, I reached the top where I could see the far away town on the banks of the Mekong River, and then headed down. I hiked down the mountain and found a different path, following across a dry creek bed to a low white cement wall among palm trees. There was a break in the wall, so I stepped in and found myself at the back of a Wat, or temple compound, the home to a dozen Buddhist monks. Most of them were just kids, sent there to live and study because they were orphans or their parents couldn’t afford to feed them. Their heads were shaved and they wore orange robes sweeping off one shoulder, as is the custom. Some were washing their clothes in a bucket of creek water, some sweeping up the ground in front of their shacks with homemade brooms, and others just milling about in the shade beside a gold statue of their patron, Buddha. All eyes fell on me when I walked onto the grounds – they rarely saw tourists outside of town and definitely none who just stumbled off the mountain into their living room, dusty and sun burnt, into their living room. They were skeptical. A couple of them waved hello but for the most part they just eyeballed me with quizzical scowls. I’d heard that Laotian people were so incredibly friendly but I honestly I hadn’t seen that. They don’t really smile or say hi and often look at you with what might be construed as downright contempt. But I’ve come to understand that it’s just a super conservative culture – so far north in southeast Asia that they’re closer to the Hmong people of China in customs and geography than their sunny-dispositioned Cambodian and Thai neighbors to the south. I said, “Sah bai dee,” hello in Lao, and moved through their temple toward the front entrance, back to the road to town. I was almost gone when I heard a feeble “hello,” behind me. It was one of the monks, a skinny boy who knew a few words of English. Then, another said “hello,” and another asked me “Where you from?” I walked back to chat with them and the monks gathered around, now eager to show off whatever hesitant English they knew. I asked to take a photo and they agreed, though a few shy ones ran away or hid behind their friends when I took my camera out. I snapped a photo but none of them smiled. The most outspoken monk, probably only 10 years old, round faced and covered with mosquito bites, expressed his skepticism by stroking his chin, looking at me like I’d just asked to dress up his pet goat in a pink tutu.  After the photo, I encouraged our conversation by asking their names. They went down the line and told me. “What is you name?” the skeptical kid asked. “Norm,” I said, slowly and clearly, so it was impossible to misunderstand. “Ahhh, Nahm!” he said, shaking heads in agreement. The repeated it among themselves like chirping birds, my name getting further distorted each time. They seemed intrigued by the camera so I held it up to take another photo. My new buddy assumed the same hand-on-chin pose but this time, two of the other monks had warm smiles. “Ahhh Nawhmms!” they cheered. I thanked them in Laos, “Khawp jai,” and went to shake their hands before I left. I wasn’t sure if it was ok to shake a monk’s hand, especially since I was sweaty and grimy from my hike, so instinctively I held out my fist to pound it out. A dozen Laotian monks looked at my fist and then at me and then down at my fist again. I extended it again and said, “Pound it out,” which even sounded ridiculous to me and might as well have been, “Lady Gaga shits on the moon,” because they’d never seen a fist bump before. They didn’t have TV or movies or even Internet. Everything they knew about the world and their whole lives were right there at the Wat on the side of a green and burnt mountain, only leaving for their predawn morning procession when locals gave them handfuls of sticky rice in exchange for blessings. I tried to show them that a fist bump was like shaking hands but they still didn’t get it. To demonstrate, I touched one of my fists to the other. Always attentive students, they touched their own fists together, too. “No, no, no, like this,” I said, and reached out my fist toward one of the monks. He finally got it - slowly, tentatively, he brought his gently-closed fist toward mine and… smashed the shit out of my hand. That brought howls of laughter from the other monks but at least they got the concept, and immediately they all held out their fists to be part of the new bizarre Western custom. So I went down the line, fist bumping each one, until the first monk wanted to do it again and soon it was a production line of pounding it out. For the second and third rounds I mixed it up with fist bump into the fake explosion, and then the fist bump-explosion-into making it rain, complete with the proper sound effects. We were all big smiles and unabashed laughter now, completely forgetting where we were and even who we’d been only minutes before. The next logical lesson for my eager class was to teach them the soul shake - where you pretend to form a joint between your fingers and smoke it after the fist bump and explosion and the rain - but my judgment got the best of me. It probably wasn’t a good idea to share that with impressionable religious disciples.  “Ahhh say ah Nawwwhhhh-si!” they yelled, and I didn’t bother to correct them. After saying too many goodbyes, all accompanied by fist bumps, I managed to take one more photo of them in action before heading out of their Wat and back to town. By now, even the skeptical monk was laughing. I can only imagine if they’re still practicing the fist bump today? Pounding it out with explosions and rain in between prayers and chanting? Maybe one will even fist bump the shiny-headed, rotund gold statue of Buddha in their Wat, or ‘Uncle Buddha’ as the little children call him? A hundred years from now, spectacle-wearing British anthropologists will descend upon northern Laos to study these hill tribes. They’ll congratulate themselves on a groundbreaking discovery - indigenous Buddhist monks actually recount their history through a ritual of handshakes. They’ll scribble furiously in their field notebooks, later to be published and debated in the halls of Oxford, interpreting that a fist bump tells about when two clans met to trade tools and spices, fiery explosions when they went to war, and finally the life-giving rains of the monsoon season. During their research, these scholars will hear faint mention of some nebulous oracle they call, “AhhSayNawwwhhm-Si,” a strange griot who descended from the mountain one day to teach them the ritual before disappearing just as quickly. Of course they’ll have no way of knowing that he wore Nikes, drank local beers by the dozens and looked more like Uncle Buddha than he’d prefer, so it will have to remain our wonderful little secret. -Norm :-)  I recently met a new friend in Cambodia, a very kind and conscious American woman from Denver who is traveling in Southeast Asia. She asked me a question so insightful I had to write a blog to answer it properly. Here is her inquiry, paraphrased: When I travel to poor countries I rarely take photos of people. I see so many art shows with photographs of the impoverished but it seems these people are no longer sentient beings - they become impersonalized backdrops at dinner parties, objectified as oppressed beings. I struggle with this. How do you feel when you photograph people who live in poverty? Here is my answer: First off, great observation! I think about that all the time as I travel or live in Third World countries and photograph people, many of them living in desperate poverty. I ask myself, “Am I just being a tourist in their suffering? Am I one of those people taking photos who think, ‘Oh look at all the starving dirty people in hovels - these pictures of their suffering will look great on my Facebook! My friends back home will think so highly of me. I feel SO good about myself for taking an hour out of my day to go visit their slum/orphanage/village, and now that I’ve got the photos I can go back to my air conditioned luxury hotel.’" My answer is always “Hell no!” but that’s the stark reality of too many tourists I see. A while back I even read an article about a South African hotel that was replicating the impoverished shanty experience. They weren’t bringing people into the shanty towns to let them experience a small part of the life of the poor, but were mocking it by building their own shanties complete with a few high-end amenities, right on the hotel grounds. That’s just dead wrong. But what about the casual traveler who can’t help pulling his camera that costs more than the local people in his finder make in two years? So much of photographing people as you travel comes down to your intentions, but you also have to communicate that intention, often within seconds and without words. I travel into some of the most impoverished areas in the world and take photographs without conflict or any problems with the locals. In fact, when I leave I’ve spread good will and hopefully helped them in some tangible way…AND still got authentic photos I’ll cherish. How do I do that? 1. When possible, I ask people if I can shoot a photo of them. Of course that loses spontaneity but if we've already made eye contact, said hello, or they see me, I'll smile and ask politely if I can take a photo, and then thank them profusely afterward. It may not sound like much, but it shows respect when you ask permission. 2. Many times I compensate them - a dollar here or there for taking their photo and sticking my nose and camera into their business. They’re always appreciative of that, no matter what the amount. 3. I ask myself how I would feel if someone stuck a camera in my face at that given moment. If I was eating dinner with my family or worshipping or in a compromising position then I might construe it as rude, but generally if someone is kind and interested in me as a human being, not just a an object for a photograph, then I’d be happy to have them document our connection. 4. Sometimes I take photos with them, not just of them. Once we’ve said hello, exchanged a smile or a laugh, and it feels appropriate, I’ll ask if I can take a photo with them, side by side as new friends. I’ve always found people to be honored and excited to be seen as such. 5. More than anything, I try to use the photo and my experience in their homeland to help them. I do that by writing about their lives, telling their stories to the world. Whether it's a blog, a fundraising campaign, or a whole book about their existence, that's my way of creating awareness for who they are and what help they may need on a bigger scale. 6. I educate myself about their country, the conditions of their lives, and the social ills affecting them, and then always make a donation before I leave. Instead of giving money to beggars on the street (which is often counterproductive by encouraging more begging and exploitation of children) I make a donation directly to a credible charitable organization that’s serving them. 7. Lastly, I smile and try to show love and respect to anyone I meet, regardless if I photograph them or not. I think it's so important to do that - my way of showing that I acknowledge them as fellow human beings and equals. Everywhere I’ve gone, I’ve found that respect and friendship are commodities just as powerful as money. *** -Norm :-)  I’ve visited so many Buddhist temples in Southeast Asia I’m suffering from TOS – Temple Overload Syndrome, a common malady among travelers who seemingly spend their days pointing high-priced cameras at anything old and/or religious. However, something struck me the other day that made me contemplate the actual core beliefs of the religion I see celebrated and worshipped every day around me. At a temple here in Laos, I saw a hand painted sign that translated the basic Buddhist principles into English. I’ve never before seen these basic teachings broken down so simply, and was so impressed I had to share. Here in Laos they practice Theravada Buddhism, the form also most popular in Thailand, Cambodia, Malaysia, and Sri Lanka. The world’s most famous Buddhist, the Dalai Lama, practices Mahayana, or Tibetan Buddhism, though all Buddhism is essentially the same at its core – stressing purity of thought and action, letting go of desires and wrongdoing as a path to liberation from suffering. All of this builds good karma, which benefits you as you pass to the next life, as they believe that you’ll be reincarnated as a higher or lower being based on how you lived your current life. Instead of heavy dogma and theological exclusion, I can testify that Buddhism is more about peaceful acceptance and coexistence with all living things. It is not a religion that emphasizes being the “right” one or converting followers - it is not in conflict but complementary to the beliefs of anyone who tries to be a good human being, especially those of compassion and service. Buddhism teachings are built on spiritualism and naturalism, and the simple everyday practice of good deeds. Theravada Buddhism teaches the following principles: Have the right thoughts. Have the right goals. Speak the right words. Perform the right deeds. Earn a living in the right way. Make the right effort. Be intellectually alert. Meditate. *** -Norm :-)  How dangerous (or safe) is commercial air travel? Airline accidents occur at a rate of one per 1.2 million flights and the odds of dying in a plane crash are about 1 in 11 million. In fact, when the National Transportation Safety Board compiled data from all plane crashes between 1983 and 2000, they found that 53,487 people were involved and 51,207 had survived. To put that in perspective, the odds of dying in a car accident are around 1 in 5,000 over your lifetime, so airline travel is immeasurably safer. Of course airline travel is so frightening because it seems so out of our control, but here’s the astounding and encouraging part - 95.7 percent of people involved in a plane crash survive. That’s incredible, and yet the data confirms that even in the most serious types of crashes, more than 76% of passengers survived. What is your Q? Industry insiders talk about your ‘Q,’ which is the death risk of any passenger per randomly chosen flight. From all data collected over the last 10 years, the Q was 1 in 60 million, significantly higher than previous 1 in 11 million fatality numbers, so airline travel is getting even safer. Why does it seem like there are more tragic plane crashes? The reason is twofold – our perceptions, and the media coverage. Studying the New York Time front page over the decades, plane accidents have been reported 1,500% more than auto hazards, 6,000% more than cancer, and at a 600% clip more than HIV and AIDS stories. Basically, the media loves making front-page headline news out of our plane crashes. Our perceptions also play a key part, understandably so because the tragedies are on a mass scale. Instead of 2 or 3 people dying in a car crash, you have 200 or 300 in a plane crash when they happen. We tend to tune out the day-to-day bad news in small chunks but stop and fixate on the big scary stuff. But whether you live or die in a plane crash is still completely out of your control, right? Not at all. The European Transport Safety Council found that 40% of the fatalities in plane crashes were survivable, which means that out of the 1,500 accident fatalities they studied, 600 people should have lived. When do crashes occur? More than 80% of all crashes occur during the first three minutes of takeoff or the last eight minutes before landing. That +3/-8 is so crucial for maintain safety. Very few accidents occur at high altitude cruising speeds when the flight is basically automated. Wet and icy runways are the leading cause of accidents. Is there a safer part of the plane to sit? This question is controversial within the field of airline safety. In 2007, Popular Mechanics magazine issued a report after studying every plane crash as far back as 1972. They concluded that sitting in the back of the plane was the safest place to be in the event of a crash. Their data showed that you were 40% more likely to survive a plane crash sitting in the back than the front of the plane. They reported that rear cabin passengers had a 69% survival rate in bad crashes, while those who sat near the wing and in the rest of coach had a 69% survival rate. It was most dangerous to sit in first and business class, where there was only a 49% survival rate. The only comprehensive study of its time, the Popular Mechanics “the back of the plane is safer” theory became the popular wisdom. However, recent research disputes any proof that the rear is safer. The reason is that every plane accident is different so you can’t formulate one universal safety number for all of them. Sometimes the plane crashes tail first; sometimes front first, on one wing or the other. Also, by delving into not only plane positioning by front-middle-back but seat-by-seat fatalities, there was no correlation with sitting in then back and survival. They did find that bigger planes were safer in the event of a crash because their size gave them more energy absorption, or “crush ability.” So if sitting in the rear doesn’t make you safer, what does? Your survival comes down to one thing: the exit row. The Five Row rule. Professor Ed Galea at the University of Greenwich in London has done the most detailed modern research into plane crashes and fatalities and came up with one theory: those who sat within 5 rows of an exit row survived at a much higher rate than everyone else. His Five Row Rule stresses accessibility to the exit in case of a crash as the #1 determining factor of who survives. For that same reason, you’re significantly more likely to survive if you sit in an aisle seat instead of by the window. The bigger and wider main exit doors in the front and the back of the plane offer the best chance of evacuation in case of an accident. What exactly kills people in crashes? Contrary to common perception that the impact of a plane hitting the ground is what’s most fatal, the toxic gases and smoke from aircraft fires in the event of a crash kill most people. Upon impact, fires or engines explosions often occur, quickly rising up to 2,000 degrees, a flash fire that consumes everything. How long do you have to evacuate after a crash? Studies conclude that in the event of a crash, you have a 90-second window to evacuate safely. Longer than that and the fire from outside the plane burns through the plane’s aluminum skin. In the airline industry this 90-second window for evacuation is called “golden time.” Will flight attendants help you? It’s best not to count on flight attendants herding you safely to evacuation, as 45% of the time they are incapacitated and cant lead you out. Interestingly enough, flight attendants are trained to look for ABP’s as they call them able bodies passengers, to help in the case of a disaster. As you board and they smile and greet you they’re actually scanning for passengers who are healthy, physically fit, sober, alert, and maybe had some emergency training – like doctors, military, fire fighters, or police officers. Flight attendants will count on those ABP’s to assist in event of an emergency. Who survives? Like we learned, even 30%-40% of fatalities in crashes are preventable. Basically, those who evacuate, survive, so it all comes down to getting out efficiently and within that 90-second window. There are several factors that speak to who will evacuate. 31% of the differences among people’s evacuation times depend on their personal characteristics like age, gender, and girth. The stark reality is that older, fatter, and less physically fit passengers are more likely to die, and females more so than males. But there’s a huge factor in survival that goes beyond physicality. Almost 50% of the difference in evacuation times between passengers is explained by inexperience and lack of familiarity with fleeing the plane. Basically, who’s alert and paying attention and know what to do. What goes wrong with evacuations? It sounds simple - everyone stand up, walk to the exit, and file out in an orderly fashion. But in the event of a plane crash it’s never that easy. There’s smoke and fire, people screaming and crying, the force of impact, injuries, and mass confusion. In these times, your mind basically goes into shock and even the easiest mundane tasks become alien. When thrust into such a dire and remarkable situation, you’re mind searches to match the current situation with memories of past situations in order to process it. When your brain doesn’t find a match (or if you haven’t trained for it), your mind gets stuck in a loop of searching for the correct response, a condition the military calls ‘dislocation of expectation.’ People freeze up under those conditions - they pause to look for social direction and leadership instead of acting, called ‘toxic immobility.’ For instance, Seatbelt Panic is a common problem that delays evacuation. In their panicked, dislocated mindset, passengers tend to pull the release, not push release. Simply passing through the aisle and knowing and following basic emergency procedures wastes valuable time, the chance of fatalities mounting with each passing second. The Federal Aviation Administration states that 61% of fliers don’t pay attention to emergency procedures. They attribute a sense of fatalism among fliers to this inattention – they think ‘if the plane goes down, it’s out of my control.’ So they go through the motions of putting their seatbelt on loosely, falling asleep, not noticing where the exits are, and drinking before or on the flight. Therefore, they make crucial mistakes when faced with an emergency. As an example, most passengers believe you can survive for up to an hour without an oxygen mask if the plane decompresses, while in reality you only have about 15 seconds before rendered unconscious. They believe they have plenty of time to evacuate a burning plane, while they only have 90 seconds. What steps can you take to be prepared? Try to book your seat near an exit row and in an aisle seat. Once you board the plane, look for the two closest exits and count how many rows away they are, and memorize those numbers. If the plane goes black or is clouded in smoke, you’ll be able to feel your way along and know how far to go to reach the exit. Pay attention to emergency instructions and even repeat some of them out loud. It’s found that if you’re visibly attentive, the passengers around you will be so, too. Stay awake, especially during takeoffs and landings. Don’t drink alcohol, make sure your bags are stowed beneath the seat in front of you, keep your shoes on, take off your headphones and be ready for action. Wear long pants, long sleeves and closed-toed shoes that are laced up. In the event of a crash there will be smoke and fire and also could be glass, metal, and other harmful fragments on the ground you have to navigate. It’s pretty scary that they also recommend you don’t wear stockings or synthetic fabrics that could melt right to your legs under high temperatures. If you’re traveling with your spouse or children, talk about exactly what to do and formulate a plan. Let your kids know that you’ll be putting your oxygen mask on first before theirs. Very importantly, put on your seatbelt correctly. It should be snug as possible and over your upper pelvis, not your stomach. In the event of a crash, every centimeter of slack in your seat belt triples the G-Force you’ll experience. The pelvis is equipped to withstand and distribute large amounts of force while a belt over your stomach could cause internal injuries. In the event of a crash what should you do? God forbid, if it comes to the moment when you realize the plane will crash, how can you prepare? At that point, everything they’ve taught you and everything around you will either help or hinder you survive. The emergency crash position can really save your life. Place your head on or near the seat in front of you so it will have less space to whip forward and collide upon impact. The seat in front of you is a big part of your safety system, designed to catch and slow you in a crash. Each seat has a special hinge that regulates deceleration, acting as a big crash pad, basically. (So THAT’s why we have to put our seats in the upright position when taking off and landing!) For that same reason, the bulkhead row in the front of the plane can be really dangerous. Plant your feet on the floor as far back as possible – they tend to fly forward upon impact which causes broken bones in the feet and legs, impeding your ability to walk and endangering you and everyone sitting next to you. When your oxygen mask drops, put it on immediately, then put it on your children, and then look around if other passengers need assistance. Get a shirt or any extra piece of clothing ready – you can put it over your mouth as a smoke guard during your evacuation. Take note of the exit rows again, go over your plan, and put on your life vest. Stay low as you’re evacuating. DO NOT try to bring anything with you or take the time to grab your carry on bags. You’d be amazed how often people try to do this and how much time it wastes. Don’t inflate your life vest until you are outside of the cabin. Don’t wear sharp shoes like high heels on the inflatable ramp and one you slide down, get far away from the aircraft while encouraging the other passengers to do the same, while staying in a tight group. Call 911 and look for emergency vehicles and follow all instructions. *** A plane crash may be one of the most frightening things that can happen to us, but by awareness and a little planning, your chances of surviving are much higher than you’d expect.

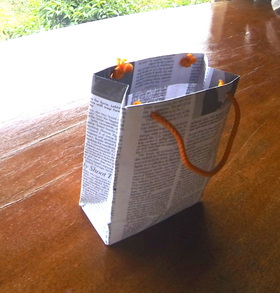

In the United States alone, 30% of our trash is discarded packaging from the things we buy. Think about that; an astounding 1/3 of what we toss into the garbage is senseless paper and plastic products just to encase the crap we purchase. We produce upward of 80 million tons of packaging waste per year. The good news is that 60% of those materials are recyclable. The bad news is that we only recycle 13% on average. Even worse, we use 1 billion plastic bags per year, or 60,000 every 5 seconds, and recycle only 1% of those. We understand that waste is bad, in concept, but what to do about it? Try to elect environmentally-friendly politicians? Help fund conservation organizations? I say, start small. I saw something yesterday that I loved, and wanted to share. I was visiting Sothy's pepper farm in rural Kep, Cambodia, where they're known for their fiery, tasty pepper just like Napa valley is known for good wine. (By the way, if you ever get a chance to visit Cambodia, do so - it's a super beautiful, chill country.) After a short tour I bought a small bag of pepper kernels to send back to my mom in the U.S. They placed it in this little shopping bag, hand made from leftover newspaper. Of course that's mostly out of necessity - in this poor country, buying a custom shopping bag would cost more than the pepper in it. But I could tell they took a lot of pride in making these little custom bags - the creases were perfect, the folds, flawless, and they even ran some orange string through holes to form the bag's handles. During the tour they also explained that they use no chemicals or inorganic fertilizers when growing their pepper plants, they reuse water, and I saw solar panels and wind turbines for power. I applaud their ingenuity. In a country with so little, with so many people hungry or eking out a meager existence on $1 or $2 a day, nothing goes to waste. I've seen a little kid build a toy car for his younger brother out of a plastic oil can with sticks for axels and leftover spools for wheels. I think we can learn something from them. Don't get me wrong, they have massive social environmental problems, themselves, but that doesn't mean we can't try to adopt the things they're doing well. So for those of us who enjoy the wealth and privilege of living in the United States, what would the positive environmental impact look like if we started eliminating even half of the packaging and paper waste we produce? How many people could we help if finding creative and practical uses for our trash became a cottage industry? How fast would our world change once we saw these little changes adding up to a huge swell of positive action, that the power to build a better world was in the hands of individual people like you and me, not governments or organizations? Many countries are already way ahead of us in this movement, no matter where they are on the economic strata, but we're starting to pay attention, whether it's inner city rooftop gardens, neighborhood cleanup days and community gardens, or even a new line of jeans released by music star Pharrell fabricated from recycled plastic bags that were polluting our oceans. All we need to change the world is to: 1) care, and 2) take action. I applaud the people at this pepper farm and in Cambodia for creating these cool little bags. It's a good start. -Norm :-) PS If you've seen an example of cool, innovative conservation in action, please drop me a line and share.  What are the 10 most popular sports in the world? I was shocked to see what was on the list, and that other sports with big time popularity like auto racing were left off. But to get to the bottom of these rankings I realized you have to look at what countries have the largest populations, not by sport. Of course football (soccer) is number So any sport widely played in Asia, India, etc. is going to be high on the list. 1. Football (soccer). 3-3.5 billion players and fans, especially popular in South America, Europe, Asia, Africa, etc. (pretty much everywhere!) 2. Cricket. 2-3 billion players worldwide. The most popular sport in countries with huge populations, Pakistan, India, Indonesia, and also the UK and Australia. 3. Field Hockey. This was shocked the hell out of me, but in fact field hockey is the 3rd most popular sport in the world, played and cheered on by 2-2.2 billion fans in Europe, Africa, Asia, and Australia. 4. Tennis. This makes sense, as tennis is a world sport enjoyed by about 1 billion people across the globe. 5. Volleyball. Insanely popular in many countries (like Nicaragua and Cambodia, two places I've lived where they play it everywhere,) it needs very little equipment and can be picked up by anyone. 6. Table Tennis (ping pong.) Wow, ping pong is one of the top ten sports in the world? Wow, ping pong is a sport? I guess it is the way they play it everywhere in Asia, about 900 million strong. 7. Baseball. Ahhh finally a U.S. Big Three sport shows up on the list. Baseball is played by about 500 million people, not just in the United States but is massively popular in the Dominican Republic, Puerto Rico, Nicaragua, Cuba, parts of South America, and Japan. 8. Golf. Getting out on the links and teeing off is enjoyed by 400 million people, mostly in Europe, the United States, Canada, Australia, and the upper crust of any society. 9. American Football. 410 million fans. American football, also called Gridiron abroad, is massively popular in the U.S., and has pockets of fans in Canada and England. 10. Basketball. 400 million fans. Hoops rounds out our top 10 list of most popular sports, but I demand a recount. With the rise of playing and watching basketball virtually everywhere on the globe, I predict we'll see this sport in the top 10 within a decade. |

Norm SchrieverNorm Schriever is a best-selling author, expat, cultural mad scientist, and enemy of the comfort zone. He travels the globe, telling the stories of the people he finds, and hopes to make the world a little bit better place with his words. Categories

All

Archives

October 2022

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed