The island was silent. Still. Peaceful. Like I had found it in 1999 when I stumbled upon Boracay Island while backpacking around the world.

Since then, the diminutive island in the central Philippines has become one of the most popular tourist destinations in the region, with more than 2 million visitors last year.

Ranked as one of the best islands in the world by the New York Times Travel, Condé Nast Traveler, and many more, it’s since become a hotbed of commercial chatter, with music blasting, excited gaggles of language, and verbal assaults from solicitors trying to get you to sign up for a sunset cruise.

This is Boracay.

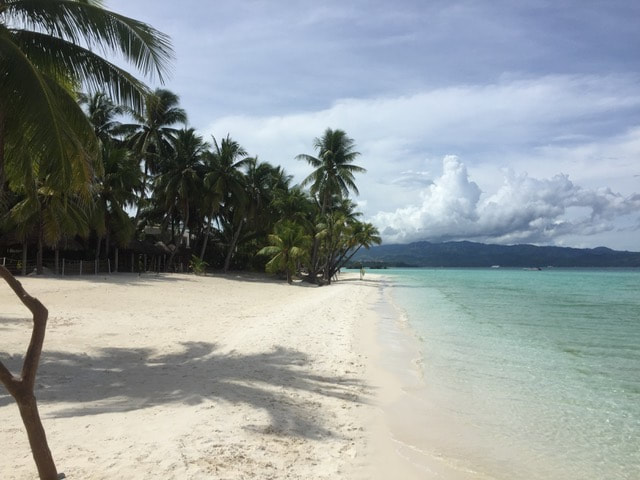

Or, this was Boracay, I should say, because it’s now eerily silent. Instead of tourists and touts, sun worshippers and solicitors, I could hear birds chirping in the palm trees, children’s laughter a kilometer down the beach, and dogs barking as they played gleefully. Ocean waves.

It was both a reminder of what the island used to be and how bizarre a situation it finds itself.

I can assure you that this was no vacation, as the island resembles little of the Boracay we’ve come to know and love.

After walking the entire span of White Beach and back again, I estimated that about 95% of the businesses are closed; boarded up, blacked out, cordoned off. Where there used to be a red velvet rope in front of a bustling nightclub, barbed wire is now strung.

A lot more are quasi-open, their rolling metal doors halfway rolled up, a glimpse of a few plastic chairs and cautious Filipino voices emerging from the darkness within.

When my guide and I make it all the way down to the more private and secluded Diniwid Beach, I check in on one of Boracay's most iconic spots, Spider House.

It's hard to even describe Spider House, as it's a series of caves and openings built into the sharp rocks of a cliff, expanded into a home by a British family in the 1980s and later into a unique hotel. With a restaurant and bar on a wooden deck built into the rocks, where you could jump right down into the turquoise ocean below, Spider House was special.

But now, it’s dark and gloomy, a big iron gate chained and padlocked closed, with dust and cobwebs accumulating. When I call out, a surprised security guard comes down the rock stairs and tells me that Spider House is closed – and won’t be reopening, as the government is seizing the property for building code violations.

The luxury resort on the steep hillside next to Spider House is still completely burnt out and smoke-stained from a ravaging fire months ago, but never rebuilt.

Yet they're busier than ever, thanks to the fact that more locals (who may not be able to swim) are hitting the ocean, as well as a head-scratchingly confusing beach safety coding system that no one understands and everyone ignores.

A security guard with a shotgun stands watch over a graveyard of mattresses, freshly scrubbed and laid out in the sun to dry – finally their chance to do so since the hotel has no patrons.

To me, it all had a Lord of the Flies vibe; the iconic 1960s book in which civilization breaks down and is reconstructed in a more primal manner when a group of boarding school kids become stranded on a remote tropical island.

But the construction on Boracay is more literal. Everywhere you turn, there is work ongoing, like the whole island has been ripped open and disemboweled. Most of D-Mall’s walkway is gutted, with an oddly-small new sewer pipe running the span.

On the main road, backhoes and trucks sit unattended, blocking traffic. Cavernous ditches are cordoned off with yellow tape. Water fills in puddles and pools on the road, splashing mud on beleaguered pedestrians and moto drivers queued up to squeeze through.

“Did it rain today?” I ask my trike driver. “Wala rain,” he says - no rain.

“Half a road is better than no road,” my trike driver comments, sensing my consternation.

It’s also quite conspicuous that very few people seem to be working. It’s as if all of these projects were started with gusto the first week when government inspectors and media were watching, but then abandoned.

That's a scary proposition, especially since Boracay was nearly 20 percent through the expected six-month closure (when I was there to visit.) Very quickly, there was talk of delays, and that was even before 26 illegal sewage pipes were discovered on White Beach.

Regardless of the fine print, the light is at the end of the tunnel for Boracay’s closure, so we should be happy that everything will soon be back to normal, right?

Before the confetti falls and the band starts playing, I think it’s important to recognize the many lives that have been irrevocably altered since the Philippines’ most popular tourist destination hung a Closed sign. Unfortunately, the shutdown caused a significant human impact, with many honest, hard-working Filipinos working and living on the island the collateral damage.

With their livelihood disappearing virtually overnight, possibly tens of thousands of workers took planes, boats, and a whole lot of buses. They fled to Manila or Cebu, where they're still trying to get jobs in call centers; to Siargao or El Nido, hoping to get new jobs in these tourist hot-spots; or, just home to the province where they could be with family and hope to get by.

The sudden draught of income is also tearing families apart, as husbands are forced to go to Iloilo or Cebu to look for work, and children are held out of school because there’s no money for a uniform or books.

The closure also recalibrated the local economy in unexpected ways. For instance, prices on staples, canned goods, and gasoline have actually gone way up since the shutdown. I even noticed a significant breakdown in services, as I waited for half an hour at the airport to get a trike, since few drivers are bothering to show up (and I don’t blame them.)

It’s hard to find a silver lining as stomachs growl and candles are lit when there’s no money for the electric bill, but I did see something uplifting: the locals have the island to themselves again.

Slowly but surely, unburdened from armies of tourists, lofty prices, and the constraints of 12-hour work days, the island’s residents are coming out to play again, like Boracay of yesteryear.

“The first few days, when there were soldiers and police and TV cameras, the locals mostly stayed away,” says Fernando. “But people started emerging more each day.”

Laundry is hung to dry on a tree, in front of a hotel that used to cost 12,000 Pesos per night (about $250). At sunset, the small number of people left congregate on the beach in front of the reggae bar to celebrate, like survivors of a zombie apocalypse.

At the iconic Nigi Nigi Nu Noos, an open-air bar that I remember from my first visit in 1999, a band plays that evening, and I count more people on stage than sitting in the entire crowd.

When I climb the steps to Real Coffee Shop, my favorite place there for years, I startle the staff, as they’re not used to foreigners wandering in. They’re playing cards, and the loser gets their face written on in black marker. There’s laughter all around when I ask to take a photo of the lady who’s obviously losing, judging by the scribble all around her big smile.

This is the spirit of the island I’ve come to know and love.

And THESE are the people who won’t give up, despite the hunger and hard times knocking on their door.

All they have to do now is survive, one day at a time, together.

-Norm :-)

RSS Feed

RSS Feed