Located only 35 miles outside of Manila in the upscale lakeside region of Tagaytay, Taal is a remarkable feat of geography and geology alike.

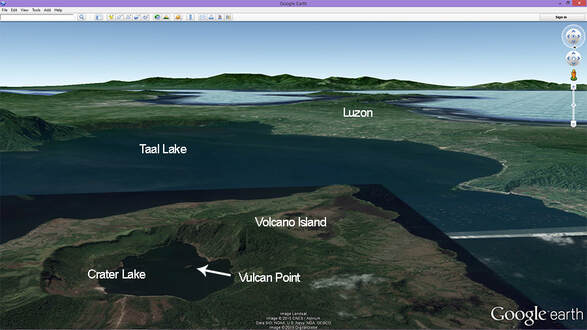

Get this: the Taal Volcano sits on an island in a lake in the middle of a volcanic crater on a larger island, which sits on a huge lake on the giant island of Luzon.

That’s like something out of a Pirates of the Caribbean movie…except it’s too fantastical to be made up. According to my research, it’s also the only one of its kind in the world

Mount Pinatubo provided one of the largest eruptions in the world in 1991, causing the overnight evacuation of the USA’s naval and air force bases nearby. That’s also why there’s so much seismic activity in the Philippines (aka earthquakes that scare the shit out of you).

Taal, which means native or original in the Philippines aboriginal language, is also notable because it’s one of the lowest volcanos in the world, cresting at only 1,020 feet above the onyx-colored beaches, lakeshores, and tropical jungle below.

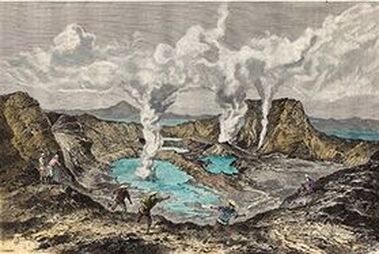

The most powerful of all Taal eruptions took place in 1754, when the volcano raged smoke, fire, and ash a full 200 days nonstop from May 15 to December 1!

“The volcano quite unexpectedly commenced to roar and emit, sky-high, burning flames intermixed with glowing rocks which, falling back upon the island and rolling down the slopes of the mountain, created the impression of a large river of fire.”

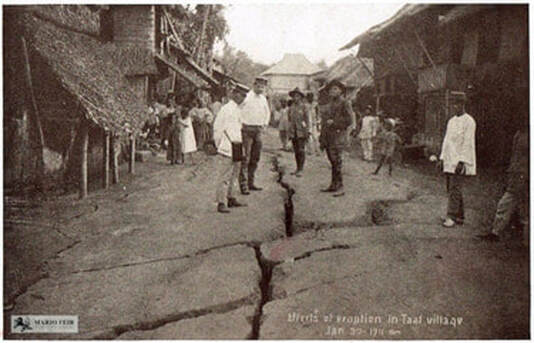

By mid-morning, a blanket of dust and ash settled on Manila, covering streets and the inside of homes, leaving a thick layer on floors, furniture, and all surfaces. In total, that eruption shot about 80 million cubic meters of debris into the air, dissipating it over an area of 770 square miles. The titanic sound from the eruption was heard more than 600 miles away.

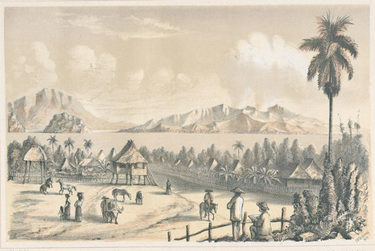

At that time, there were seven barangays – small fishing villages or farming communities – on the island. They were all completely wiped out, sparing no man, woman, child, and turning the 702 cattle on the island into smoking carcasses.

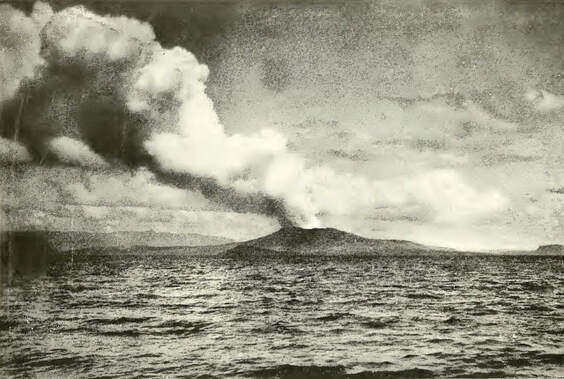

Remember that this was well before seismologists and meteorologists could measure and share data, so there was no warning, and only grainy black and white photos of the event exist.

While that was the deadliest saga in the history of Taal, the ring of fire exploded violently once again some 54 years later in 1965. During that eruption, ash and debris were shot a full 12 miles straight up into the atmosphere.

Traveling like a supercharged typhoon of ash, mud, and boulders, it screamed furiously across the lake, crushing villages and jungle canopy at the water’s edge two and a half miles away, killing about a hundred people.

The other difference was that in 1965, more people owned cameras, so there are more photos from during and after the eruption, including one shot of people on the “mainland” fleeing with suitcases in hand.

No significant eruption has taken place since 1977, but plenty of minor disruptions, toxic gas leaks, and seismic activity occur periodically. Those include rumbling threats in 1991 (when Mount Pinatubo erupted), 1992, 1994, and June of 2009 most recently. For that reason, it warrants careful monitoring with advanced scientific instruments by the Philippine Institute of Volcanology and Seismology.

That’s also where the volcanic lake’s water gets its majestic emerald color, but there are no fish under the water. That color has changed over time, too.

Before the 1911 eruption that redrew the map, the 18-mile diameter Taal lake actually had several openings because it was lower than sea level, with a green lake, a rusty red lake, and a bright yellow lake based on the minerals and gases it was interacting with. Some were so hot, steam billowed off of them incessantly.

The most telling sign of an impending eruption would be a precipitous rise in the lake’s water temperature. For example, the water temperature rose from a bath-water-like 86 degrees Fahrenheit to a scalding 113 degrees right before it erupted.

Taal will blow again - it’s just a matter of when and how big – and that’s the reason the government has banned the public from living there, so there are no official towns or barangays.

The locals, who don’t even have a name (like Taalians?) because no one is actually from there and they aren’t supposed to be there, live in makeshift nipa huts and sunbaked concrete communities, many of them built right on the volcanic ash. There are a few churches, remnants of NGOs or Catholic mission work, no electricity (only solar power and generators), and no government-sponsored roads, clinics, or public schools.

But we weren’t trying to flee the volcano this sunny day in July – we were trying to actually go to it, boating over to the island, hiking up to the volcano, and entering the crater.

Stay tuned for my account of that adventure in next month’s postcard!

Stay cool, everyone!

Norm :-)

RSS Feed

RSS Feed