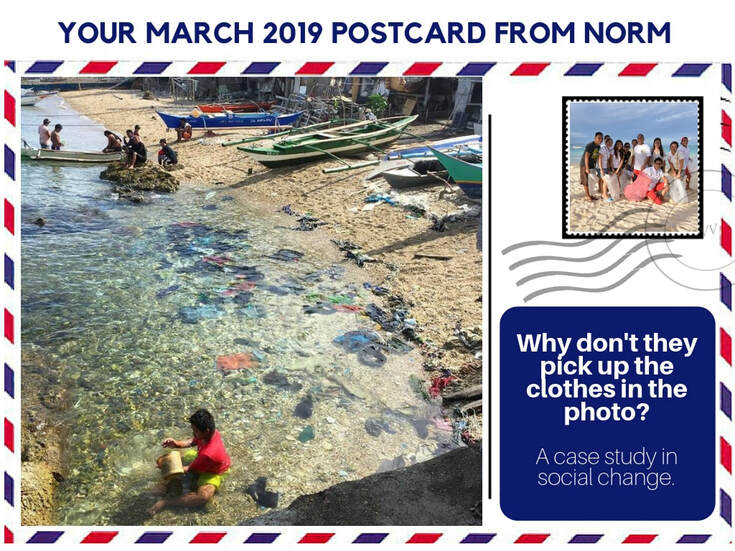

I snapped a photo, which I posted on social media with this caption:

"Wandered into a poor fishing community in Caticlan directly across from #Boracay. I saw all of these clothes in the water and at first, thought they were doing laundry (but that would make no sense in sea water, of course).

But one of the ladies told me that those were just the discarded garments that washed up from Boracay — basura, or trash."

To me, it wasn't a big deal, as I see this kind of thing every day here in the Philippines. So, I was surprised by the wave of outspoken opinions, condemnations, and even outrage that followed.

Scott, a UK expat living in the Philippines, commented, “Why aren't they picking them out of the water?”

Voytec from Nicaragua commented, “I know there is a problem with education and culture, but for me, they are just dumb and too lazy to pick it up. We have the same here in Nica.”

But it wasn’t just foreigners that were perplexed, as Filipina Alijane expressed her disbelief with, “Why is this!?”

Bray, scuba diving tour guide in the islands, followed that with, “No one has the initiative to pick it up?!”

On it went, but only one or two people tried to paint these villagers in a different light and float a reason why it was, if not right, then understandable. My old high school friend Barbara from the U.S. offered, “Maybe their island dump is already full of other people’s trash? If it happens often, they may just get tired of looking for places or ways to dispose of it.”

Again – no one is “wrong” in this discourse, but it fascinated me that this one photo could evoke such strong opinions. So, I wanted to dig deeper into the issue not from an environmental perspective, but a cultural one.

To start, do you notice how we always condemn the end user or last person on the daisy chain? For instance, NO ONE seemed sympathetic that these people were the victims of such pollution. Someone else manufactured the cheap clothing (probably China), creating even more pollution in the process, someone else purchased them, shipped them, sold them, wore them, etc. Ultimately, someone else threw them out – in a landfill, on the side of the road, or, as is too often the case here, right in a local creek or waterway that serves as a big trash receptacle and eventually washes into the ocean.

The people in the photo – poor locals living in shanties and surviving on a few dollars a day – were complicit with none of those actions, yet everyone blames them because the waste happened to wash up in their "backyard."

If these poor fishermen and their families did go through and pick all of the clothing that washed ashore, where would they put it? There isn't waste management in this tiny village (a trash truck would never make it through their impossibly-narrow sand paths!) and no dump nearby.

For people who spend most of their time eking out a meager existence, trash is a part of life and the backdrop to their surroundings and always has been.

And if they did take the time to collect everything, wouldn't it just ash up again tomorrow? Why should these impoverished locals take the initiative to clean up after rich tourists from the other side of the island (Boracay).

Conversely, show these same humble villagers a photo (or headline) about Flint, Michigan, and they'll be twice as shocked and perplexed why the wealthiest country in the world doesn’t even

provide clean, poison-free water to its citizens.

Superimpose this scenario onto your own lives, and we might not hold well under our own scrutiny. Do you clean up trash that isn't yours? I'm sure you would if someone littered in your front yard, but these people don't own the beach (or the land their huts stand on).

When was the last time you went to a public park and started picking up trash? Or a pile of trash that sat at the end of your street?

I try to do my part, but I'm guilty of this too, of course – selective indifference.

I just walked by a discarded soda can and a pile of cigarette butts on the way to a coffee shop to write this.

There's another, more clinical way to look at this one snapshot – or any social issue on a larger scale: through the prism of Maslow's Hierarchy of Needs.

In summary, this psychological theory states that if people are hustling daily just to eat, keep a roof over their heads, or stay safe, then we can't expect them to be "self-actualized." That's a fancy way of saying that they're concerned with more lofty precepts like the Greater Good, personal development, the meaning of life, etc.

This is a perfect real-life example of that theory as, to the people in the photo, there’s no tangible benefit to picking up the clothing and trash (unless Philippines’ Pesos start washing up!).

Is it a matter of edu-ma-cation or poverty?

So, are they just uneducated and that's the problem?

While there may be a correlation between a lack of education, poverty, and litter or blight, we can’t attribute that to causation – and it doesn’t tell the whole story. Wealthier or educated people may be more ecologically conscious on the whole (just an assumption), but they don’t necessarily pick up the trash and clean up themselves – they pay for others to do it most of the time.

Additionally, there are a whole lot of CEOs and politicians that went to Ivy League schools who are choosing to do the wrong thing and pollute our world just to squeeze out a few extra dollars.

But we can take clues from something called The Broken Windows Theory, a sociological study that earned its merits by helping transform New York City from a cesspool of crime, filth, and community hopelessness in the 1980s into the (relatively) safe and shining example of a major city it is today.

Broken Windows Theory was an academic concept introduced by Stanford University researchers, James Q. Wilson and George Kelling in 1982. It proposed that even minor "disorder and incivility” within a community opened the floodgates for more serious crime.

Wilson and Kelling's theory was based on a study where they placed two identical cars in two vastly different neighborhoods – one in the South Bronx and the other in a nice area in California. While the car in the Bronx was quickly broken into, had its tires stolen, etc., the abandoned car in California stood undisturbed.

That is, until the research team came back to the Cali car and intentionally broke one of its windows and then, left it again.

What happened next laid the groundwork for their theory, as the previously-untouched car was quickly vandalized and broken into, too. This reinforced (if not proved) their assumption that when people see and experience minor transgressions that are obviously tolerated or unpunished, far more chaos will ensue - and escalate.

The Broken Windows Theory became the premise for sweeping change in New York City under Police Commissioner William Bratton from 1990-1992, when he ordered a massive crack-down on impropriety in the Big Apple’s notorious subway system, including swarms of visible police and a zero-tolerance policy on relatively minor infractions like panhandling, graffiti, turnstile jumping, drinking in public, urination, and more.

They also took their efforts to the streets and trains above, where they cleaned cleared the sidewalks of petty drug pushers, prostitutes, beggars, solicitors, unlicensed vendors, and scam artists like those who jumped out and started washing your window at traffic lights.

Of course, many questioned the common sense behind this all-out war against PETTY crime, since muggings, murders, major drug deals, rapes, and serious theft was rampant. But the Broken Windows Theory proved sound and the transformation to the city was nothing short of miraculous.

In fact, by the time Bratton resigned as Police Commissioner in 1996, not only were the subways, sidewalks, and street corners safe and civil once again, but major felonies were down 40 percent and the homicide rate was cut in half!

It turns out that social depravity – no matter how seemingly minute – was such a slippery slope that the whole city inadvertently snowballed down it.

Of course, the United States is one of the biggest offenders when it comes to consuming non-renewable natural resources, creating greenhouse glasses, and producing waste. What’s even scarier is that many politicians on one particular side the aisle still don’t even acknowledge climate change or the environmental disaster we've created.

But this problem won’t be solved by regulations and policies alone (although those are sorely needed), as governments are usually just the tail that wags the dog.

For instance, the island of Boracay – the #1 tourist destination here in the Philippines - was recently shut down for six months when Philippines President Rodrigo Duterte observed it had turned into a "cesspool" and ordered it cleaned up.

With Boracay closed for an environmental overhaul, thousands of locals making a humble living as taxi drivers, waitresses, tour guides, and clerks lost their only source of wages. Many of them were barely making it to begin with and sending money back home to support their families.

Still, despite the hunger, hard times, and uncertainty they faced over those six months, they supported the cleanup for the most part. These brave unwitting activists championed the cause, taking pride in their island that would soon be one of the cleanest in the world.

Once Boracay reopened as a textbook example of conservation in action (and a stern warning to offenders), others took notice. More islands and communities started "cleaning up their act" proactively, worried the government would come in and shut them down, but also because they now realized the potential for change.

We are largely products of our environment and adopt the norms, mores, and expectations that are placed upon us – a base anthropological definition of culture. Without getting into the whole debate about nature vs. nurture (go watch Eddie Murphy’s Trading Placesto learn about that!), people in any society, neighborhood, tribe, or even family will conform to the culture of that group.

So, in order to clean up the beach in that photo…and this part of the world…and our entire globe eventually, we have to initiate a culture shift, first.

We have to make it unacceptable to litter, pollute, deface, vandalize, and harm our planet. And there needs to be social status and affirmation awarded to those who do act as agents for change.

Any true solution will come from people, as we basically need to “make it cool” to care about the environment. Expectations need to be raised and universally adopted. Children need to be taught to love, respect, and care for the world we live in, and, in many cases, children need to teach their parents, too.

Consciousness is the start of that, and already there’s a small glimpse of hope as environmental action is the #1 political concern for Millennials in the United States.

I also see the early days of a massive culture shift here in the Philippineshumble environs, too.

In Dumaguete, where I used to live, I saw patrons implore their favorite local restaurants to start using metal straws instead of plastic ones (cleverly labeled 'Straw Shaming').

On the idyllic little island of Siquijor (rumored to be haunted and rife with witches!), a few of my local friends started organizing clean-up days at their beaches, invite tourists to join in. These became fun, must-attend events, and they even cooked big feasts for the volunteers.

The photos, stories, and friendships returned home with these tourists, and beach cleanups became almost a bucket-list item for conscious travelers.

One by one, municipalities are cutting down or eliminating their consumption of single-use plastics, too. Electric vehicles are slowly but surely popping up on the roads.

When I traveled to the incredibly wild and remote island of Batanes last year, far in the northern sea, I was dazzled by how the locals kept their island spotless and organized when it came to waste and recycling, despite a stark lack of resources, education, and technology.

Here in the Philippines, the movement is growing organically, picking up steam at a faster rate than I ever anticipated.

Recently, Manila Bay, a toxic stew of plastics, trash, chemicals, and other waste, became the cause célèbre when thousands of volunteers - especially youth – mobilized to pick up trash and start the long road to rehabilitation.

On my birthday in February, I met two really cool Filipina sisters at a bar. Chatting over (many) drinks together, they told me that they had a clean-up event to attend early the next morning, shattered my preconceived notions. (And gaining my respect when they actually made it there, despite the hangovers!)

These new friends even travel (on their own time and dime) to outside of Manila on the weekends, volunteering to clean up the beaches there, too.

Bolstered by media coverage and social media sharing, the concept has mushroomed into a movement. Don’t get me wrong – these micro-efforts probably haven’t even amounted to more than a drop in the bucket, and we need to magnify that effort by 1,000 – no, 10,000 – to see the real impact.

This momentum (and measured progress) will continue to grow until we reach a Tipping Point, as author and social statistician Malcolm Gladwell calls it.

Thanks to these small sparks that ignite a blaze of consciousness, the culture of how we treat our Mother Earth will truly have changed.

At that point, we might look back at the photo in this postcard and think not, “Why didn’t THEY clean it up?” but, “Why didn’t WE clean it up?”

-Norm :-)

RSS Feed

RSS Feed