Welcome to Boracay.

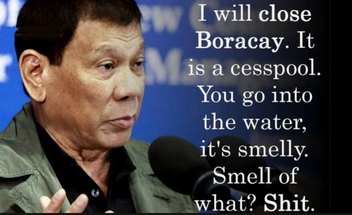

The island has also been in the news lately, as the Philippines President, Rodrigo Duterte, upon a recent visit, called the once-pristine island "a cesspool." In an unprecedented move, he ordered it closed to all tourism until the island's environmental issues could be addressed.

The problem? Basically, a couple million people a year create a lot of human waste, and the island has no sewage processing plants. So, everything ends up in the water system and flushed out to sea, where it's changed the ecosystem so much that a huge field of green algae plagues the shores of the island. Gross, right?

Virtually overnight, the island went from an everyday population of around 50,000 people to only several hundred. It's a surreal situation, leaving people scrambling to figure out if they could stay, had to go, or how they could make a living.

What's lost in the international headlines and local political debate is the plight of the 26,000 people who live and work there, as well as many more who commute there by ferry every day to work. In fact, nearly the entire populace of the island – and the province of Aklan on the neighboring island – make their living off of tourism.

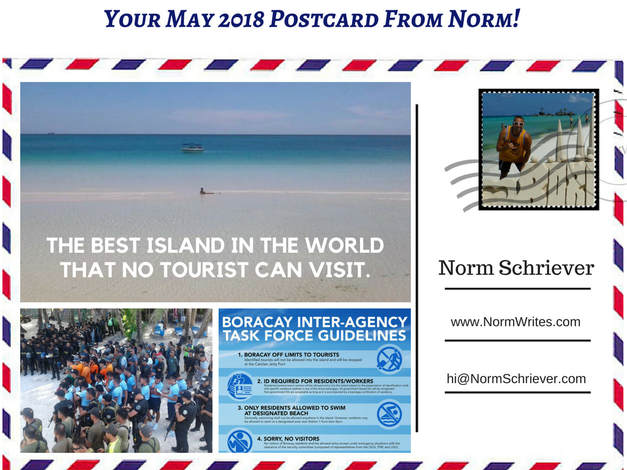

I’ve had a long and notable relationship with the island and its people, which I'll recap in this postcard.

I first stepped foot on the sands of Boracay in 1999, another impromptu stop on a trip backpacking around the world with my good American buddy, Phil. The island still had very few tourists on it, as I remember just a smattering of guest houses and nipa huts in the middle of the jungle. While the beach was spotless and beautiful, it was still wild, and the small number of foreigners tended to be German guys there to engage the surprising number of Filipino transvestites. Yes, you read that right. There were even signs to attract "Third Sex" patrons at beauty parlors and other businesses.

While I didn’t partake in that local tradition, I did do a whole lot of swimming. I was coming off running (or attempting to run) a marathon in the nearby city of Cebu, and my feet were so tore-up and bloody from wearing new sneakers that I could barely walk, limping around the sand path for the week we were there.

What does silver screen starlet Liz Taylor have to do with Boracay? Learn more about the history of the island here.

But I could still swim, and did so for an hour every morning and afternoon, dodging the small local Barka fishing boats while watching the most beautiful sunsets I’d ever seen.

That was Boracay, and I gave it little thought after we left for the next exciting destination.

I came back to Boracay in 2013, 14 years after I first visited. Having just moved to Asia six months prior, I wanted to try life in the Philippines as an expat instead of my former stop, Vietnam. So, I came back to Boracay and lived there for several months.

Already, it was unrecognizable. That little sand path gave way to a larger sand lane that spanned the whole 3-mile beach front. Those small guest houses and huts were now modern resorts, shops, and restaurants.

But it hadn't lost what made it unique – the perfect white sand beach like talcum powder running through your hands. The beach and the shallow turquoise waters were pristine, and you couldn’t even find a bottle cap, cigarette butt, or plastic bag discarded anywhere.

The people living there were still locals, too, and there was a sense of community and family among the island’s inhabitants. While there were a lot of tourists already, I had no idea how much it would grow in the future – or what was coming next.

On November 8, 2013, Typhoon Yolanda (international name: Haiyan) slammed into the Philippines, killing tens of thousands and burying parts of whole coastal cities in water. With wind gusts up to 278 km/h (235 mph) and 10 meter (30 foot) sea swells, it was considered the strongest typhoon in recorded history ever to make landfall. Yolanda was heading right for the isolated and unprotected island of Boracay, too.

I tried to evacuate to the neighboring mainland along with thousands of other stranded tourists and locals. But we were turned away since the Coast Guard shut down all boat traffic off the island 48 hours before the typhoon.

Looking around the island, it registered that we'd all be underwater if those sea swells did come. Resigned that I might be facing my demise, I stocked up on supplies, too, said my goodbyes and headed down to a little bar on the beach to watch the storm come in until it grew unsafe.

Luckily, the heart of the typhoon blew just south of Boracay, so the island was spared the horrors that devastated Leyte, Samara, and Tacloban.

I took some video and wrote blogs about the typhoon that went viral, earning me interviews with international media like CNN and more.

Soon after, I was able to leave Boracay, and I eventually moved to Cambodia.

The experience of being on Boracay for the typhoon and its aftermath was my inspiration as I wrote my most recent travel memoir, The Queens of Dragon Town.

After I moved away to Cambodia, I still managed to visit the Philippines once a year, including Boracay. I enjoyed checking in on old friends who live there (Mox, Hayden, Anthony, Marix, etc.) and introducing new buddies to the island (Scotty Powell, Judd Reid).

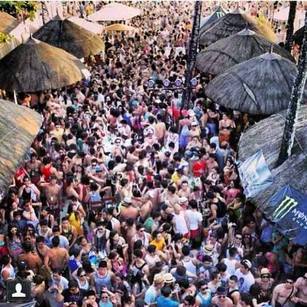

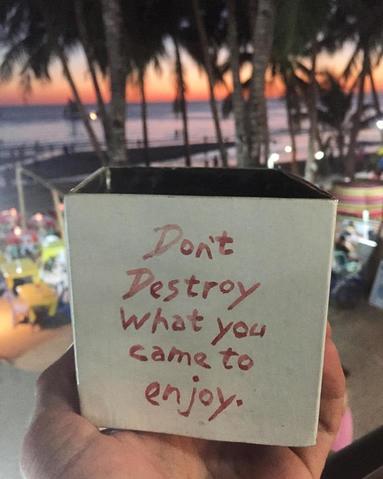

But the island that used to be wild and pristine was now overrun with tourists. In fact, last year, more than 2 million tourists came to Boracay, including 375,000 Chinese and 356,000 South Koreans, who have a reputation for being loud, rude, littering, treating locals poorly, and doing just about everything they could to denigrate the environment.

However, all of those tourists did bring in more than 56 Billion Pesos in revenue, so the island was now a turnstile of commercialism – and the beach and the water suffered, growing noticeably more spoiled and polluted every time I visited.

I still soaked up the sun and wallowed in the waves for a few days but, longing for the Boracay of yesteryear, I started researching the culture and history of the island, too. To learn a little bit about what I discovered, check out these 50 facts about Boracay.

This year, I’m living not so far off in Dumaguete, but had no intention of returning to Boracay until…

My bond with Boracay just took an unexpected turn.

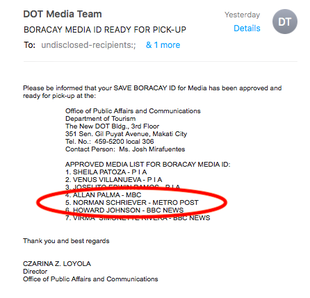

Even as the island is sealed off to tourism, they are allowing a small number of media to visit, documenting the story of its closure and environmental rehabilitation. Today, I received an email that my request for a media credential was approved by the Department of Tourism.

As a hobby, I write a weekly column for the humble hometown paper here in Dumaguete, the Metro Post. Evidently, that was enough for them to grant me a media pass to visit the island – one of a handful of non-Filipinos who will be allowed on Boracay over the next few months (together with representatives from the BBC, the Philippines Information Agency, and others).

I’ve enlisted my dear, old friend, Hayden, who is an accomplished and trusted tour guide there, to help me arrange interviews with locals, business owners, and government officials.

What will I see when I get there? What stores does Boracay have to tell? What will the future hold for the world’s best island, which was a victim of its own popularity?

I look forward to finding out – and sharing those answers with you.

-Norm :-)

RSS Feed

RSS Feed