I shot up with a start, soaked with sweat and completely lost with the vertigo that a deep sleep had brought me. I had no idea where I was. Actually, I had no idea where I was, no idea when it was, and no idea who I was. It was a horrible feeling, and I was still breathing heavily as my half-asleep mind spun in panic to try and lock onto some detail of my life, but I could not.

I was in a dark room with the curtains drawn, the busy workaday noise of diesel trucks and motorcycles drifting in from the street outside. It was oppressively hot, the only breeze in the room coming from a wobbly ceiling fan. I rubbed my eyes and tried to focus, but I still felt like I was falling down an elevator shaft, desperately trying to grab hold of something to slow my fall. Was I in the South Islands of the Philippines? No wait, in Chang Mai? No, I’m pretty sure that was last week. That meant I had to be Bangkok, right? But I had been in Bangkok twice already, so that couldn’t be it.

I swung my legs off of the creaky bed and put my feet on the floor. I couldn’t even remember the date or be sure of what month it was; maybe it was March? Or February? I wrestled to pull off my shirt, but it stuck to me because it was so wet with sweat, and then I threw it on the green tile floor. I had been traveling way too long — it felt like wherever I went I left a piece of me, and pretty soon there would be nothing left if I wasn’t careful. I rifled through the drawer on the cheap nightstand by the bed. There was a menu and a letter in some language I could not decipher, a book that looked like a Bible or a Koran — I couldn’t tell which — that I pushed to the side, and a pad of stationery. It listed the information for the hotel on the header: the Nuweiba Hotel in Cairo. Damn, I was in Egypt — I hadn’t even been close. In that dizzying kaleidoscope of my year backpacking around the world, I’d seen and heard and felt so much — maybe more than any one person was meant to in such a short time — that my psyche couldn’t keep up and process it all, but at the same time my spirit was vaulted to heights that I never imagined possible. What dream was this — what dream of a life that I was walking in? There was something I was missing, but I couldn’t quite wrap my head around it.

A few days later I took a train from Cairo down to Aswan, near the Sudanese border. Traveling within Egypt was always a tricky endeavor: I was advised not to take the train, nor sit near the windows, because militant Islamic fundamentalists would often take pot shots at the tourists, hiding in the sand dunes with rifles and causally sniping. Then again, taking a car ride between cities was even more dangerous. Egypt has the highest rate of road fatalities in the world and they drive like absolute maniacs, literally speeding up and swerving to try to hit pedestrians. They could care less about lanes and stoplights or even going the correct direction down the street, instead cursing and honking and jamming five lanes of traffic into a two-lane road, running smaller vehicles, donkey carts, and old ladies carrying firewood off into the ditches. So when I had to get down to Aswan I thought my odds of survival were better in a window seat on the train. We were scheduled to depart at 6 a.m. but I was there early, just in case they scammed me with a fake ticket again. I carried an oversized backpack that held all of my possessions in the world: a few pairs of clothes, notebooks bursting with my words, and souvenirs like Turkish rugs and jade statues. As dawn broke on the train platform, columns of light marched over the dusty skyline, armies sent to warm the earth and send steam rising from the cold metal train cars. One by one, the train windows were illuminated with reds, pinks, and yellows reflected from the sunlight. The track was mostly deserted except for a few vendors selling steaming bread out of covered baskets and a sleepy conductor; it was surprisingly quiet for such a chaotic, bustling city.

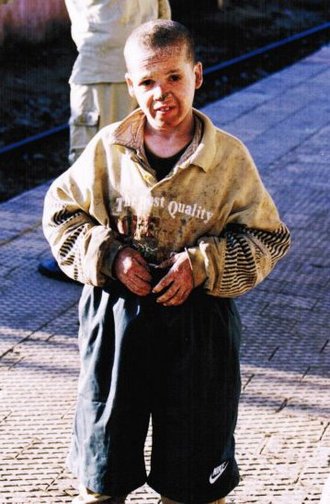

I felt someone’s presence behind me. I half-turned and noticed a child huddled in the shadows behind a concrete column ten yards down the train platform, peeking out at me. He was shrouded in darkness so I couldn’t make out the details of his form, but he was staring curiously at me while still trying to remain hidden. Since he was my only company on the train tracks and I had time to kill, I figured I’d make him feel welcome, so I turned around to face him and smiled. He jumped further back into the shadows, afraid at first, but then I gave him the thumbs up sign so he knew I was saying hi to him and that it was safe to come out. He hesitantly stepped into the sunlight. My companion looked to be around 8 years old, though it was hard to tell because he was so filthy and malnourished; he might have been 13 for all I knew. He wore layers of dirty rags covered with train soot and black shoes that were falling apart. I looked closer and saw that his skin was dried and diseased, covered in scales that plagued most of his body, including his face. Even on his nose the skin was cracked and permanently marred. His fingers were withered and raw with red sores where they weren’t covered with dirt.

At first his appearance shocked me, but then I made sure to smile at him again to make him feel comfortable. He’d probably never seen a foreigner or even a white person before, something I found surprisingly often when I trekked through remote parts of Asia or the Middle East and the jubilant kids would run up and touch the blonde hair on my arms. He stared up at me with big black eyes, taking in every detail. This boy was obviously a street kid with no roof over his head, no one to look out for him, and not enough to eat. The thought occurred to me that maybe he lived somewhere near these tracks and got his food by rummaging through the garbage cans and others’ waste at the train station. Of course, I’d seen plenty of street kids over my last year of traveling; in fact, I’d seen much worse — people dying right in front of my eyes — but there was something different about this kid, something warm and alive in his eyes that registered much more than just the pain I expected.

There was an empty soda can on the track near my feet. I nudged it a few times with my sneaker like I was dribbling a soccer ball. He looked up, intrigued. I kicked the can in his direction and a huge smile broke out on his face as he realized I was playing soccer and including him in my game. He stepped closer and kicked it back to me. We kicked the can back and forth a few times, both chuckling at how quickly our new friendship had formed. I said my name in English and then said a few words in Arabic. He tried to respond, but when he opened his mouth only a grunt came out, even as he strained his throat muscles. It seemed like he was also mute. Damn, that’s rough.

A chill from the morning air overcame me, so I zipped up my fleece jacket. Was he cold? If so he didn’t show it, even though he was only wearing flimsy rags that were falling apart, the remnants of a matching sweat suit that was so yellowed with age I couldn’t even tell what color it originally was. I noticed that on his sweatshirt were printed the words “The Best Quality” — now if that ain’t irony I don’t know what is.

Since he couldn’t talk, I held out my hand for him to give me five. He didn’t know what I was doing at first, and then his face lit up when he realized that I wanted him to slap my palm. I bet that this kid was used to no one wanting to touch him or go near him because of his skin disease. He probably had no one to hug him, and that thought broke my heart. He had no chance to live a normal life: He would never be safe, never be well-fed, never be able to sleep indoors, never get an education, never know what it feels like to be loved and have family around him, and get married and raise children. No matter what this kid did he was destined for a short life of pain, misery, and suffering. Yet it was by no choice of his own — his only crime was being born at the wrong place in the wrong situation to the wrong people. But even with all of these disabilities and detriments he was a smiling, good-natured soul, expecting absolutely nothing out of life but enjoying any little scrap of mercy it threw at him.

I felt ashamed that I didn’t appreciate my own life sometimes. How dare I complain, feel sad, get stressed — I mean, what the hell in the grand scheme of things did I really have to worry about? I sometimes felt that I had it hard, yet in my cakewalk life I had every advantage and opportunity, and very little of it was earned. I suddenly felt guilty about my own hypocrisy; sure, I was traveling and witnessing all of this stuff, but what was I actually doing to make it better? I watched him dribble the soccer ball around an invisible defender and then kick it to his new teammate. Why wasn’t I the homeless one — mute and eating out of a garbage can? Why was I instead a tourist to his misfortune, on my own grand adventure but able to head back to comfort and luxury after this year? What separated the two of us? Why were we different? Luck. Bad friggin’ luck.

It frightened me, and enraged me to my core how unfair life was. And this was just one kid on one train track in one Third World city — imagine how many billions of others were out there who were suffering and needed help. There was so much sadness in the world that you could get lost in it if you weren’t careful. How were we ever expected to overcome it? Was there enough light in the dawn to warm such endless and drowning darkness?

I motioned the kid closer and handed him a $1 bill. It didn’t seem like enough. I handed him a $10 bill. His face showed disbelief, and his big, ancient eyes registered a gratitude I’d never seen before, nor since. He looked around to make sure no one else was watching so he wouldn’t be robbed once we parted, took the money in his small, shriveled hands, and tucked it safely under his sweatshirt. If possible, his smile got even bigger, but he was not focused on the money — he had found something kind in my face and that was most comforting to him. Fuck it — I handed him a $20 bill, the last money I had with me, and closed my wallet. Thirty-one U.S. dollars could probably feed a kid like this for six months. He was now the richest urchin in the slums of Cairo, the king of his train platform.

It still wasn’t enough — these small tokens, though greatly appreciated, didn’t even come close to what I felt for him. I motioned for him to hold on and went into my bag, rummaging around until I fished my best pair of gray Nike basketball shorts and my favorite T-shirt and handed them to him. He proudly put them on over his rags. They were so big on him that he looked like a child playing dress-up in his dad’s clothes. He admired his reflection in the train window, proud of his new wardrobe like he was the luckiest kid alive.

I didn’t want to go; I didn’t want to leave him, and something had changed in me. I’d been all over the world that year, registering about 70,000 miles over six continents; I’d seen ancient wonders of the world and majestic vistas that would steal your breath, witnessed people worshiping at 2,000-year-old temples and walked in the same footsteps as mankind’s most famous explorers, but somehow, inexplicably, there on that dirty train platform with a little street kid, I had found what I was looking for: I had found my purpose. It finally clicked what I was supposed to do with all that meaning I had been carrying inside of me: I would be his voice. I would make sure that he was heard, that the world knew that he took breath. I would be the one to fight for his place in eternity because he could not, and I’d be the voice of all the underdogs — the weak, the forgotten, the scarred and stained — who ask for nothing but someone to tally their existence. That’s what I wanted to do with the rest of my life.

The train started to pick up speed and I looked back for him one last time and saw that he was looking for me, too. He waved and a huge smile bloomed on his wrinkled, dirty face. As we rolled on I watched him grow smaller, but before it all faded away I could make out a street urchin turn and walk on down the platform back into the ruins of Cairo, kicking a soda can. I stared at the seat in front of me for a long time, just listening to the comforting “gilickety-clack” of the train heading on down the line, and for the first time I started thinking about going back to a place called “home.”

Tamarindo, Costa Rica, surf, ski, snowboard, diving, pura vida, Central America, Nicaragua, San Juan del Sur, Amazon best seller, travel, adventure, backpack, hiking, sharks, Endless Summer, Robert August, memoir, fitness journey, globetrotting, perfect beach, paradise, spring break, expat, live abroad, work abroad, summer reading, around the world, great read, humor, laugh out loud, South of Normal, Pushups in the Prayer Room

RSS Feed

RSS Feed