My grandfather was lucky, some would say. He wore thick eyeglasses so he was disqualified from fighting in the first Great War, though he was only 24 at the time, and he was too old to serve in the second. So instead he settled into his comfortable career as the lone postmaster for the village. My grandfather (called Opa in German) and his family, including my mom as an infant, survived the war because his postal route took him out to the countryside, and oftentimes the farmers would trade him a few eggs or some hard-to-get potatoes or turnips in exchange for good news.

When Oma (my grandmother) was pregnant with my mom, the Allied forces strafed and bombed the village, so she had to run into the woods to hide, a bittersweet reminder that the liberators’ work was not done yet.

When the war was mercifully over, times were still tough, and their village was in the French-occupied zone. They lived in a little apartment over the post office and had to house a soldier, but he turned out to be a good guy and even brought my grandmother baby shoes for my mom when he returned from leave in France. She also got care packages from the U.S. — aid sent from church groups and school children — with fancy pencils with erasers on the ends, candy, and chewing gum, which she tried for the first time. Many were not so lucky, and the rape of young women was so rampant that the brave priest in town invited all women who didn’t feel safe to bring their bedding and sleep in the bell tower of the church. Every night for months, he locked them in there and slept on a chair at the front door, making it known that the French soldiers would have to kill him to get in.

They were not Nazis, of course, and not even Party members, but just poor, humble people trying to eat and raise their families, like most Germans were. But one always wonders, especially as I was growing up in the United States as I did during the very end of the Cold War; a time where to be German or Russian was still met with lingering suspicion. But then, one day I heard a story about my Opa that put all my worries to rest, and made me eminently proud like I cannot even verbalize. People who’d been through war and seen horrible things usually didn’t talk about it, preferring to leave it in the past and do their best to move on, so these things weren’t the topic of many conversations in my family. But I think I really knew my Opa for the first time, for he was already an old man when I was born, more through this story than I ever did in real life. It was a gift to glimpse what kind of man he was, and I loved him deeply for it — and I hoped that some of his caring heart had been passed on to me.

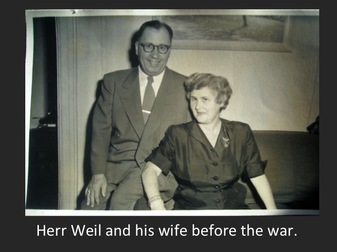

My Opa had a good friend, a man named Herman Weil, who owned a successful clothing store on the main street in their village, Stockach. Every Thursday night, they met with a few other gentlemen and played cards and drank brandy at a local restaurant, and Herr Weil’s wife was also friendly with my Oma. Heir Weil was Jewish, and as the Nazi party overtook Germany, he was arrested by the dreaded SS officers and taken away late one night. My Opa was distraught over his friend’s disappearance, and a little digging confirmed his worst fears: He had been taken to Auschwitz, herded into a rail car along with other Jews and prisoners of war and transported to the death camps in Poland where he likely faced starvation or the gas chamber. When Herr Weil arrived in the concentration camp he was assigned a prisoner number that was tattooed on the inside of his left forearm. If you want to read an accurate yet horrific account of Auschwitz, you will find none better than Night, by survivor Elie Wiesel, as he describes his first night in that same place:

Never shall I forget that night, the first night in camp, which has turned my life into one long night, seven times cursed and seven times sealed. Never shall I forget that smoke. Never shall I forget the little faces of the children, whose bodies I saw turned into wreaths of smoke beneath a silent blue sky.

Never shall I forget those flames which consumed my faith forever.

Never shall I forget that nocturnal silence which deprived me, for all eternity, of the desire to live. Never shall I forget those moments which murdered my God and my soul and turned my dreams to dust. Never shall I forget these things, even if I am condemned to live as long as God Himself. Never.

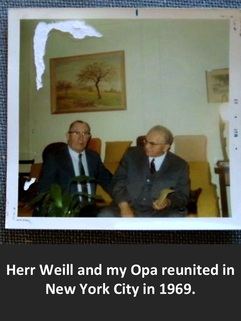

And that is where Herr Weil found himself, in striped pajamas and tattooed, surrounded by walking skeletons with sunken black eyes who would fight in the dirt over a discarded scrap of rotten bread, awaiting a certain death. My grief-stricken Opa worked every angle, called in every favor, and leveraged every friendship up the governmental chain of command to try and help Herr Weil. Opa was not a Party member nor SS, but a postmaster, but that held some pull in those days, so amazingly his campaign to beg, borrow, and barter for his friend’s freedom was successful.

But of course, Herr Weil didn’t know anything about this. One day, his prisoner number was called over the loudspeaker at Auschwitz — which meant for sure that you were headed to your death at the gas chambers, or worse, subject to unspeakable torture or medical experiments. Herr Weil thought he was a dead man, but when he arrived at the guard station they looked at him with disdain as they smoked their cigarettes and told him to “just go.” He didn’t understand. Just go, get out of here, they said, and they opened the smoke-stained death gates of Auschwitz and shooed him out of the camp. He walked from the camp on shaky legs, expecting a bullet in the back of his head, but it never came. He didn’t dare look back and when he was out of sight, he ran.

***

To read the "Sunflowers" part of this chapter, check out the book.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed