| I knew I was coming back to Cambodia to visit, and my airline tickets were booked months in advance. But I kept it a total secret so I could surprise my homie there, Kalvin “Wicced” Hang, who I hadn’t seen in about a year and a half. So I did set it up with one of our mutual friends, Johnny, who made sure Wicced would be in a certain bar after work. When I ninja’d (is that a word?) in behind him and pretended to bump into him, the look of surprise on his face was priceless. I had my tuk tuk driver film the encounter. | |

Right after 9/11 (like HOURS after), the U.S. government started cleaning out the jails and prisons and deporting Asian Americans under the auspices of national security. Thousands of guys (and some girls, too) were handcuffed and put on a plane with little or no notice, flown to Southeast Asia with air marshals guarding them, and abandoned in the airport.

These prisoners were of Filipino, Laotian, Vietnamese, and especially Cambodian (Khmer), origins. When it comes to Wicced and the rest of the Khmer deportees, they have an interesting background.

As Cambodia was devastated by the Vietnam Conflict (the U.S. “unofficially” dropped millions of pounds of bombs on the Cambodian countryside to deter Vietcong supply lines, as well as planting millions of landmines in the ground there), hundreds of thousands fled the country. That trickle of humanity became a flood during the brutal regime of the Khmer Rouge.

Most of them ended up in refugee camps in Thailand, some of them living there for decades despite the fact that the Khmer Rouge was defeated in 1978. But the refugee camps were full until 1992, when the United Nations came into Cambodia and stabilized the political climate. People re-entered Cambodia, walking into the bombed out and empty ghost towns where they grew up.

Wicced was born in one of those refugee camps, and came over with a Green Card, too. So did all of the deportees, spending their formative childhood years living in the U.S. When they were deported to Cambodia, most of them had never even stepped foot inside that country.

They were left to their own devices, with no money, no jobs, and most of them didn’t speak the language or have family to take care of them. Despite what you might think, the officials and police at the airport in Phnom Penh, Cambodia didn’t welcome them with open arms, and instantly they had people trying to shake them down for money or else they’d be thrown in an immigration prison for an indeterminate amount of time. So they’d often just have to make a break for the exit, running from the police and only safe when they hit the street.

But things didn’t get easier from there. As Wicced has told me, many of the guys ended up on the streets, and some resorted to crime just so they could eat, or started doing drugs to ease the pain and confusion of their new situation. After all, they were separated from the families – many of them removed from their wives, girlfriends, and children back home – and could never go back.

“About half of us made it,” Wicced says as he explains that many of the guys got simple jobs and worked their way up, assimilated to the culture, and made a new life in Cambodia. “And half didn’t.”

Now, thanks to Wicced and many other forefathers of the Deportee community in Cambodia, new arrivals are met at the airport, with advice, resources, money, a place to stay, and a chance at getting a simple job and transitioning into modern Khmer society. That chance is invaluable.

He’s also the definition of loyal – probably to a fault. Wicced is the guy you call at 4 a.m. if something is going down. He’s incapable of forgetting his roots, abandoning his people like society cast them aside.

But now in his 30s and a lot wiser than his hot-headed gangbanging days, he also has cautious hopes for a different future, something he alludes to more and more in our private conversations over the years.

Wicced works tirelessly to advocate for his community of deportees. That’s a major role, as every year, thousands more are sent over from the U.S. So he represents his people at international refugee workshops, human rights conferences, angles with the media, writes letters to U.S. politicians and cozies up to the Khmer elite and cocktail parties, all trying to affect change.

But don’t get it twisted – a lot of these guys were bad dudes doing bad things. But they were living legally in the U.S. with Green Cards, and joined gangs just like everyone else in their violent, disenfranchised neighborhoods. There was no lawful and legal explanation for their deportation; and there still isn’t.

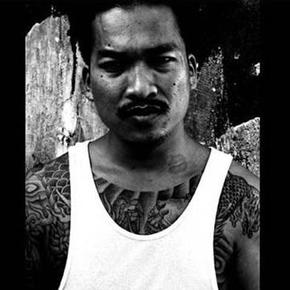

In prison, they were always outnumbered, and had to be viciously fierce and. Their prison tattoos still stand out, even since they’ve been adorned with new, fresh ink in Cambodia. They came from pretty rough places like Long Beach, California, Stockton, California, Philadelphia, PA, and Lowell, Mass. – all tight knit Khmer communities to this day.

They were Crips, Bloods, and a whole lot of other gangs and sets I know nothing about, but they had to squash all of that once they got to Cambodia. They needed each other to survive, now, as it was literally them against the world. Sometimes, when they’re at their functions or parties and drinking (which is almost any day that ends with “y”), those beefs and hostilities from the planet of American they used to live arise. But it always gets worked out with help of their elders (who are only in their 30s) and respected leaders. It has to be, because they can’t afford to be divided.

And the world has taken notice (other than the U.S.), with increasing attention paid to their cause. In fact, just when I was leaving Cambodia after my relaxed an enjoyable 10-day stay, the Cambodian government announced that they would refuse any more deportees from the U.S., essentially shutting the door on more Khmer-American refugees.

It was a trivial back-page piece of news for most of us, but a seismic shift in the geography of possibilities for Deportees like Wicced.

Respect. And safe travels, little brother.

-Norm

P.S. Here is a BBC article on the plight of the Deportees, and one by the New York Times.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed